Comics Corner – The Historic Importance of ‘Gay Comix’

For this week’s Comics Corner, we’re taking a look back at one of the most important comics in LGBTQ+ history, the revolutionary Gay Comix. This will be the first instalment in a series – think of it as a column-within-a-column – aiming to take an in-depth look at each issue of the anthology title, the stories within, and the creators involved.

CONTENT NOTE: This column openly discusses sex and sexuality. Images may be risqué, and may be considered NSFW.

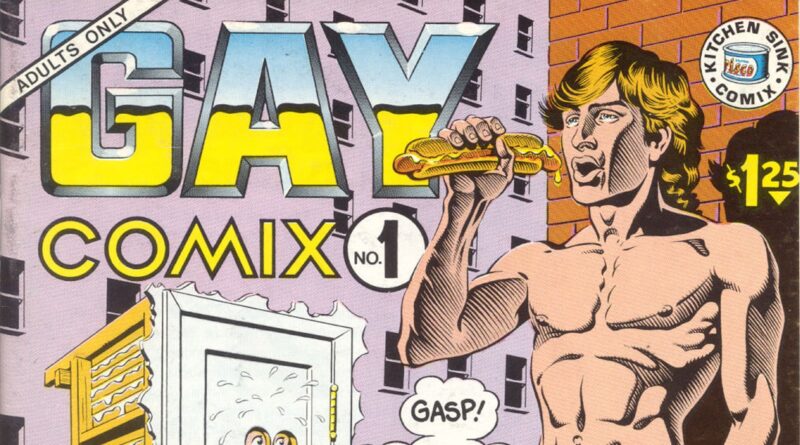

First published in 1980 by small press specialist Kitchen Sink Press, Gay Comix was an anthology that emerged from the underground comics scene. While the restrictive edicts of the Comics Code Authority forbade depictions of homosexuality in mainstream titles, underground, self-published, and small press titles created an arena where queer creators could tell stories unfettered by moralistic oversight.

While Gay Comix wasn’t the very first comic aimed at queer readers or by queer creators – it could be argued that Tom of Finland’s works, particularly Kake, takes that accolade, while other underground comics such as Gay Heart Throbs pre-date Gay Comix – but it is arguably one of the most important and longest running. Although published only irregularly, with only one issue per year between 1980 and 1985, it would run until 1998, ending with its 25th issue.

Gay Comix landed with a splash. Its first issue was emblazoned with a striking cover by Canadian artist Rand Holmes – an eyecatching full colour piece with a muscled, topless skater suggestively eating a hot-dog, with shorts that left nothing to the imagination. Perhaps knowing the intended audience’s fears – this is 1980, remember, when the gay rights movement was still comparatively young – it’s only after noticing the skater that the reader’s eye is drawn to a distracted onlooker who is literally in a closet.

The series was originally edited by Howard Cruse. While Cruse was already a well-known figure on the underground comics scene and would go on to create the seminal Stuck Rubber Baby – a semi-autobiographical tale of coming out in the deep south, set against a backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement – Gay Comix was the first time Cruse published work that was explicitly gay. It was, in effect, his own coming out.

Despite the bold cover though, Gay Comix was intended to capture the human and humorous side of gay, lesbian, and bisexual experiences of the time (sadly, trans stories weren’t a focus, at least in the first issue). Rather than the caricatures or walking punchlines that passed for gay people if any showed up in larger media, and instead of pushing the (still mythical) ‘Gay Agenda’, Cruse wanted to present comics drawn from the real, almost mundane, lived experiences and unique perspectives of the creators involved. In his editorial, Cruse wrote that the subject of the book was simply “Being Gay”, that “we’ve tried to leave our soapboxes behind and express our humanness” and that “to put it mildly, there’s more to the gay experience than can be chronicled in 36 pages.”

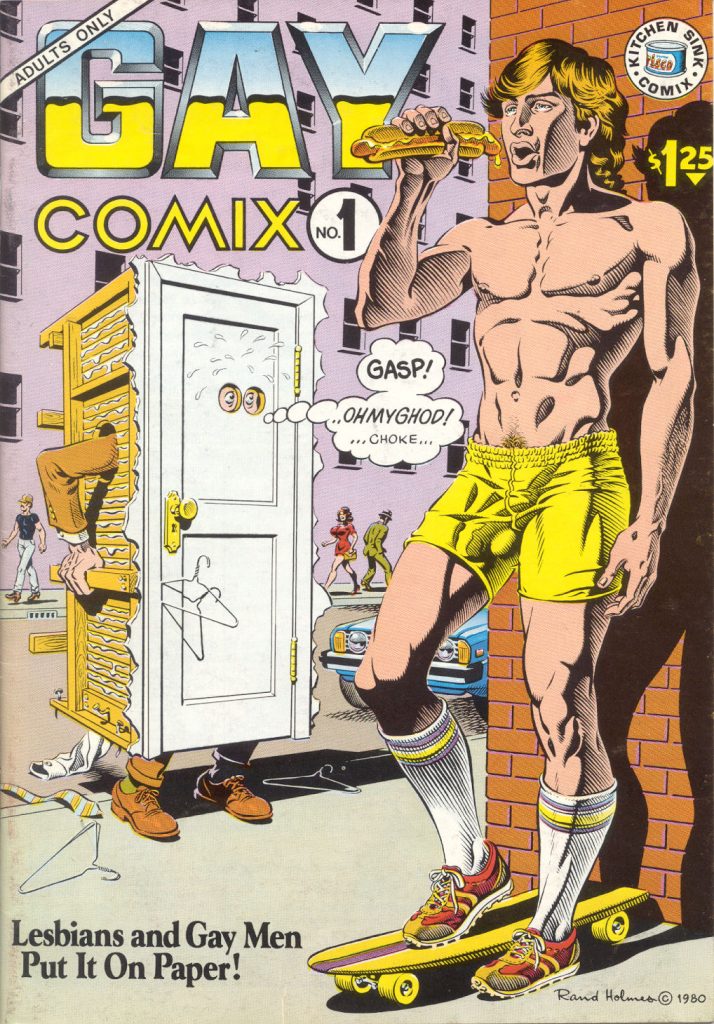

The first issue of Gay Comix opens with a bang, with the eight-page “Stick in the Mud” by Lee Marrs, already an icon in the underground comics scene. It’s a beautifully told story exploring the struggle to fit in, with protagonist Sue struggling not just with sexuality but also wider social cues. Sue grows from an unpopular child torn between wanting to be invited to play but having no interest in her young peers’ “games” of torturing animals, to a clumsy teen whose attempts to rebel backfire. A “late bloomer” with little interest in boys but her eyes drawn to girls, it’s not until university that Sue has her first lesbian experience.

It’s no glorious, self-assured moment of clarity though. Marrs brilliantly captures the ongoing uncertainty that many queer people experience, with Sue not even having the language to define her identity, and only ugly stereotypes of what a lesbian is to guide her. Meanwhile, Sue and her college roommate Joyce keep their encounters a secret, especially from Joyce’s boyfriend Jack – until Joyce moves away, and Sue and Jack end up getting married. One doomed marriage and a series of bed-hopping liaisons with men and women alike later, and Sue finds herself at her nadir: waking up in Los Angeles. Swearing off dating, Sue eventually meets Carol, the love of her life – but even after years of self-discovery and learning what doesn’t work for her in relationships, Sue still struggles to tell her how she feels. Ultimately, “Stick in the Mud” is a heartfelt story with a comedic edge, exploring the life-long search for acceptance and love that LGBTQ+ people can experience, and how “coming out” isn’t a one-time event.

Many of these themes are echoed in Gay Comix #1’s next strip, Billy Fugate’s “Fallout”. At only three pages, it’s both denser and more abstract, with the artist tormented by gremlins on the wing – a nod to a famous episode of The Twilight Zone, perhaps – as he spirals through a haze of bar-hopping, bad choices, and terrible hook-ups in a search for meaning. Another one-page strip by Fugate appearing later in the issue, “Found a Reason”, is almost a coda to “Fallout” though, with an older gay male couple simply living their lives – waking up together, going about their days, and showing that age is no impediment to an ongoing love and sex life.

Roberta Gregory’s “Reunion” follows, charting the lives of three different women from a support group, each envious of the others’ relationships and statuses, without realising the strengths of their own lives. Single mother Marta struggles to find a girlfriend who’ll accept her two young sons; Liz is challenged by the boundaries – or lack of – in her open relationship; while Nina has to overcome issues with sobriety but finds a stable girlfriend along the way. It’s a somewhat choppy, raw story, with transitions between the three women often coming mid-page and making for some jarring reading, but it’s a notable exploration of how diverse lesbian experiences could be, even when many gay women had to live closeted lives.

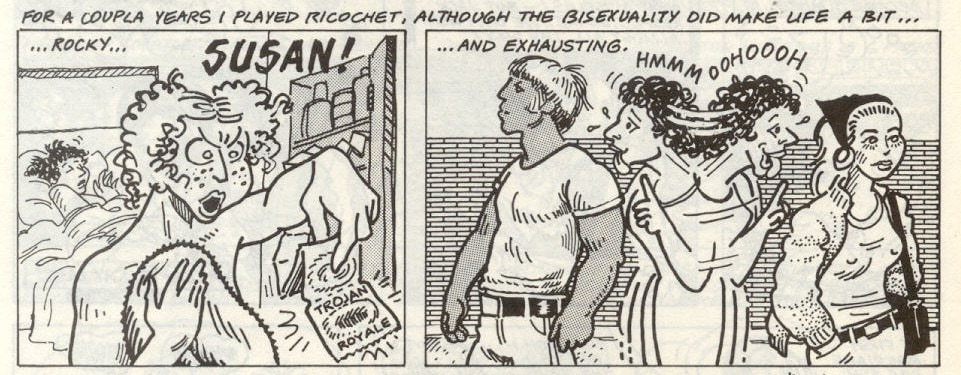

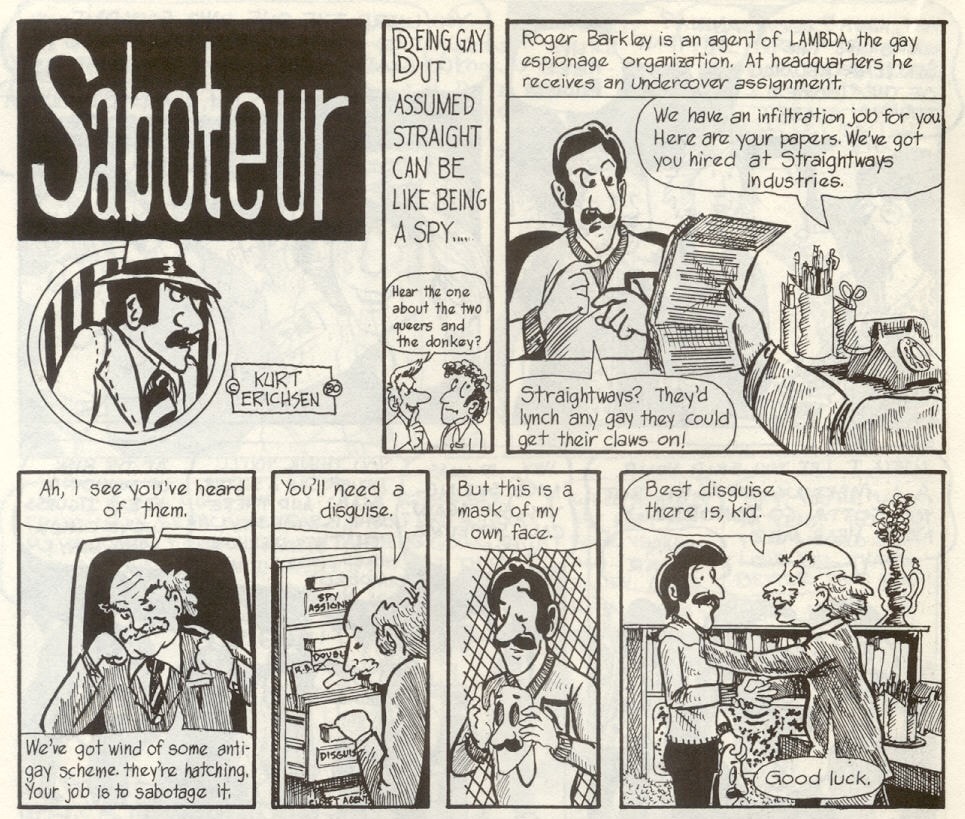

Kurt Erichsen’s “Saboteur” is the farthest Gay Comix #1 delves into pure fiction, bordering on farce. A four-page story, it sees Roger Barkley, an agent of a “gay espionage organisation” with the uncanny ability to – wait for it – pass for straight, infiltrating the nefarious Straightways corporation. A front for bigots, Straightways is cooking up a fiendish plot that would turn every gay man fluorescent purple, to make them easier targets. Thankfully, Agent Barkley saves the day, switching the active chemical for one that instead turns the bigot’s necks bright red. Let that sink in for a second.

While “Saboteur” is played for laughs – including a great visual gag where Roger has to use a strength gauge to prove he isn’t limp-wristed – there’s some clever satire in the strip too. Straightways plan to make every gay man identifiable can be seen, particularly for the time, as a commentary on the perils of forcibly outing someone, as it would (and sadly, often still does) make them a literal target. The fact that they plan to do so by chemically altering instant TV dinners is likely Erichsen poking fun at the not-so-glamorous lives of gay men though, a far cry from the “fabulous” stereotypes.

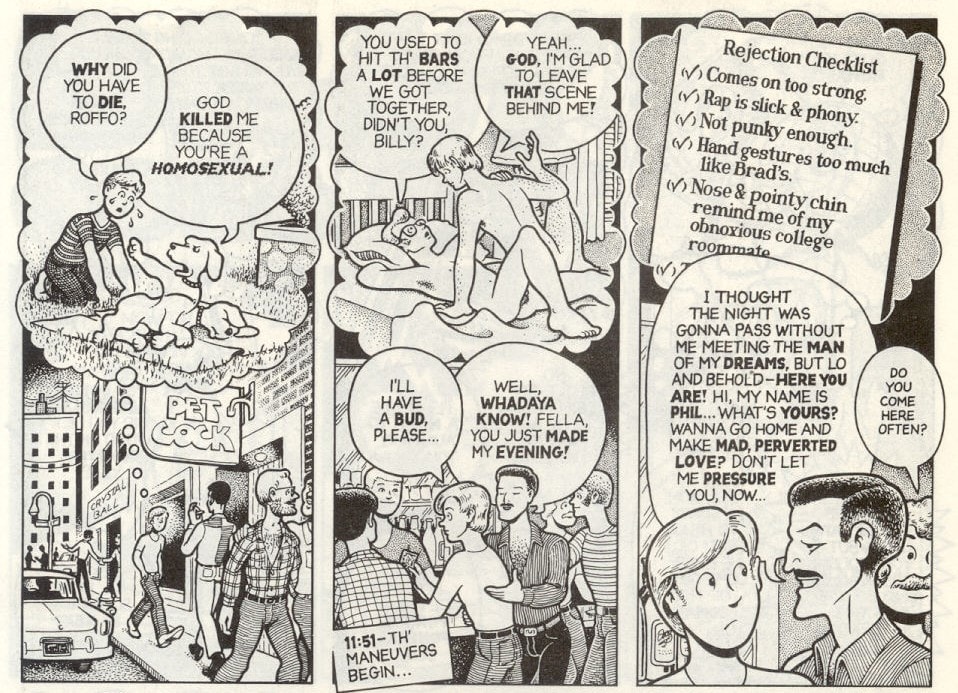

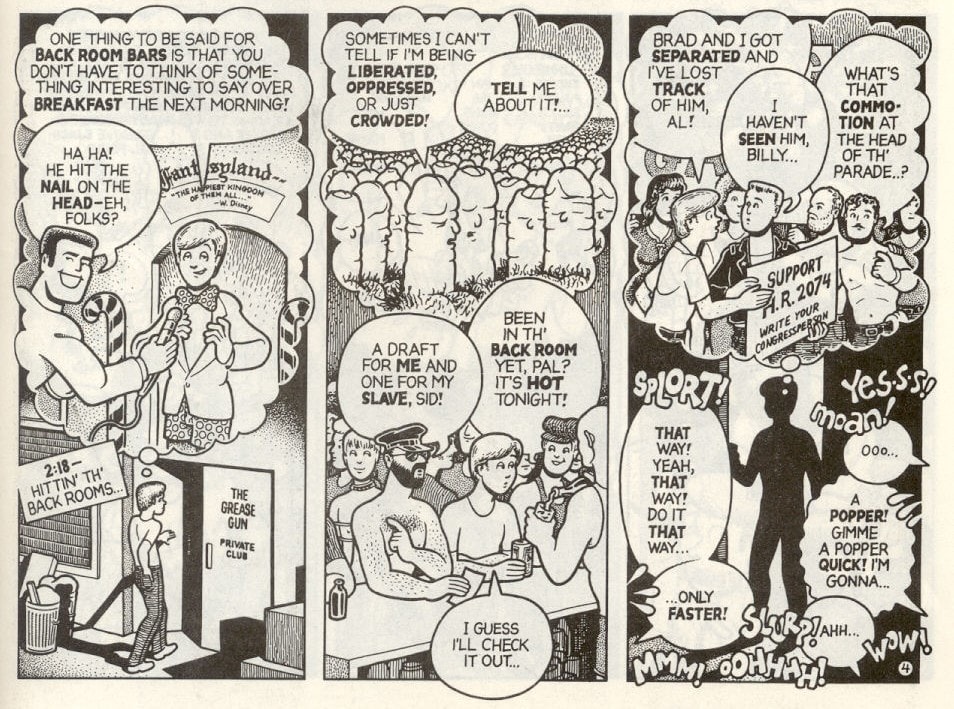

It’s Cruse’s own “Billy Goes Out” that’s arguably the star of Gay Comix #1 though. In only seven pages, Cruse packs in a tale of a lonely young gay man, drowning in a world of drinks and vacuous, meaningless sex after losing the love of his life, Brad. It’s a multi-layered tale that, on the surface, charts Billy’s disappointing night on the town, but also paints the protagonist as drowning in his own thoughts, hungry for companionship but holding every man he meets up to the impossible standards of Brad – who, it’s implied, died in an attack on a Pride march. Billy is also haunted by the bigoted words of his own uncle, and some pretty toxic internalised homophobia, thinking it’s his fault his childhood dog died because he was gay.

“Billy Goes Out” is a surprisingly complex short story, with moments of levity brushing up against some seriously dark thoughts. In one panel, Billy might be having a mental conversation with his own anthropomorphised penis, while in the next he’s remembering funerals and moments of heartbreaking loss. It also explores the dark trajectory Billy is on, ignoring men who show genuine interest in favour of detached sex in darkrooms.

Cruse’s art here shows the all the strengths and magnificent detail that would later be so strikingly used in Stuck Rubber Baby, but has a more cartoonish style that evokes newspaper comic strips. Both Billy and his imaginary penis have rounded, heavily inked features that give an almost animated appearance, balanced against detailed backgrounds and environments. “Billy Goes Out” is the most graphic of the stories in the debut issue of Gay Comix, with multiple sexual encounters shown, but a sense of loneliness haunts the pages as Cruse paints a picture of gay men desperately searching for attachment, but often simply making do with transitory experiences.

The issue rounds out with Mary Wings’ “A Visit From Mom”, a sweet, lighthearted case of presumptions and, effectively, mistaken identity. A woman calls her girlfriend to explain that she can’t come to a birthday dinner because her mother is visiting, and she wouldn’t understand their relationship because “she’s just a sweet little old lady!” However, in explaining her childhood, and how her mother had lived with her “best friend” Mrs D for fifteen years, pointedly growing lillies together, it becomes clear to the reader, if not the protagonist, that the apple hadn’t fallen far from the tree.

Nearly four decades on from its release, Gay Comix remains a compelling read, exploring the experiences of queer people in ways that still feel relevant today. Rounded out with pin-ups by Demian and Theo Bogart, the work contained in these 36 pages is both timeless and historical. Although the series is long out of print – and with Kitchen Sink Press going out of business in 1999, republication rights to the earliest issues are presumably in limbo – Gay Comix remains a key moment in LGBTQ+ comics history.