Comics Corner – The Historic Importance of ‘Gay Comix’, Part 3

Fandoms and communities are rarely singular monoliths of thought – just dive into any online forum for any given subject, and you’ll likely encounter endless debates raging back and forth with various intensity. In LGBTQ+ circles, the tension can be even greater, especially when it comes to discussions of what counts as “good” representation, or how active community members should be to “count”. Such discussions are common even now, but Gay Comix #3 was exploring them way back in 1982. Plus ça change…

Nowhere is this more clear than in the anthology’s first letter column. Considering the Kitchen Sink Press publication was still an annual occurrence, editor Howard Cruse ran a selection of reader correspondence covering the previous two instalments. Rather than pick out purely ebullient praise, the selection also included negative feedback, including one writer from Paris lambasting the second issue and complaining that “the artwork is really terrible” – a broad statement for an anthology publication, but one that showed there was no consensus on quality even in the early days of queer underground comics!

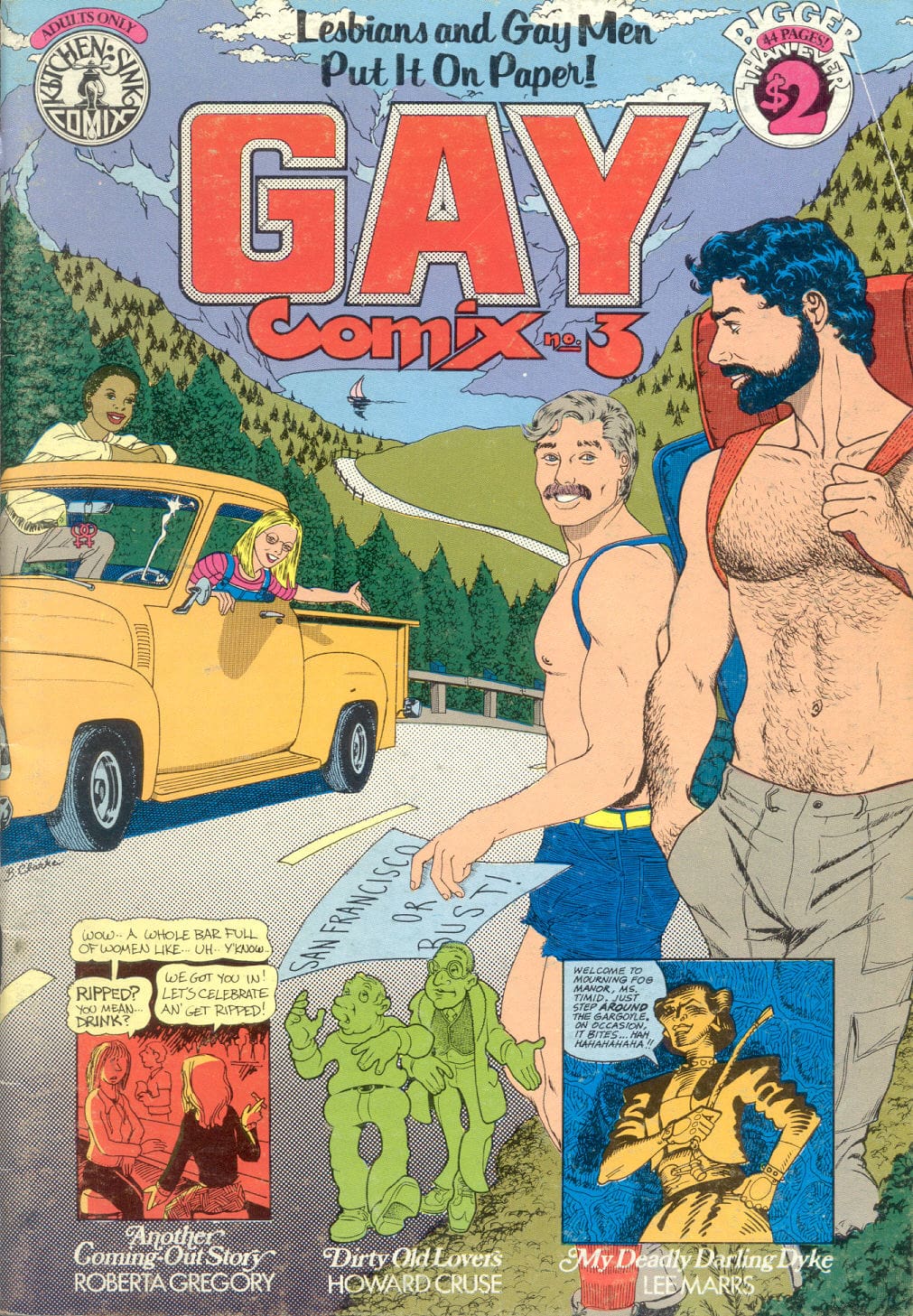

Most interestingly though was a letter from one Mary Wings, complaining of the overtly sexualised cover to the first issue and how the presence of a “giant penis on the cover has not much to do with our common culture”. This is the same Mary Wings who had contributed to the previous issues as a creator (“A Visit From Mom” in issue one, and “Child Labor” in issue two, both highlights of their respective collections), making her displeasure with the cover a particularly interesting facet of queer comics history. She also lambasted the background image of a woman with “impossible breasts that defy gravity”, which is a fair critique – given the series carried the tagline “Lesbians and Gay Men Put it on Paper!”, reductive sexualised depictions of women somewhat undermines that.

If in the present day it seems odd that Wing didn’t know the final packaging of the book until she read it herself, consider the tiny scale of the publication, and the challenges of gathering work from LGBTQ+ creators from all across the US in a pre-internet era. It’s likely that not every creator was given advance warning of the cover ahead of it going to print (and if they had been, there may not have been time or budget to make alterations). Whatever the reason, through the lens of history, such creative disagreement from even those involved in the series’ creation is fascinating.

Hopefully, Wing – who did not contribute creatively to the third issue – was more impressed with this issue’s gorgeous cover (above) by Burton Clarke, creator of the previous issue’s “Cy Ross and the S.Q. Syndrome”. In front of a bucolic landscape, the cover shows two topless male hitchhikers, brandishing a sign saying “San Francisco or Bust!”, being picked up by a pair of (for the early ’80s) lesbian-coded women. While certainly suggestive, it’s significantly less so than the first issue’s bulging penis, and even Cruse’s second issue cover, with its textual discussion of kinky sex, in a visual ode to MAD magazine.

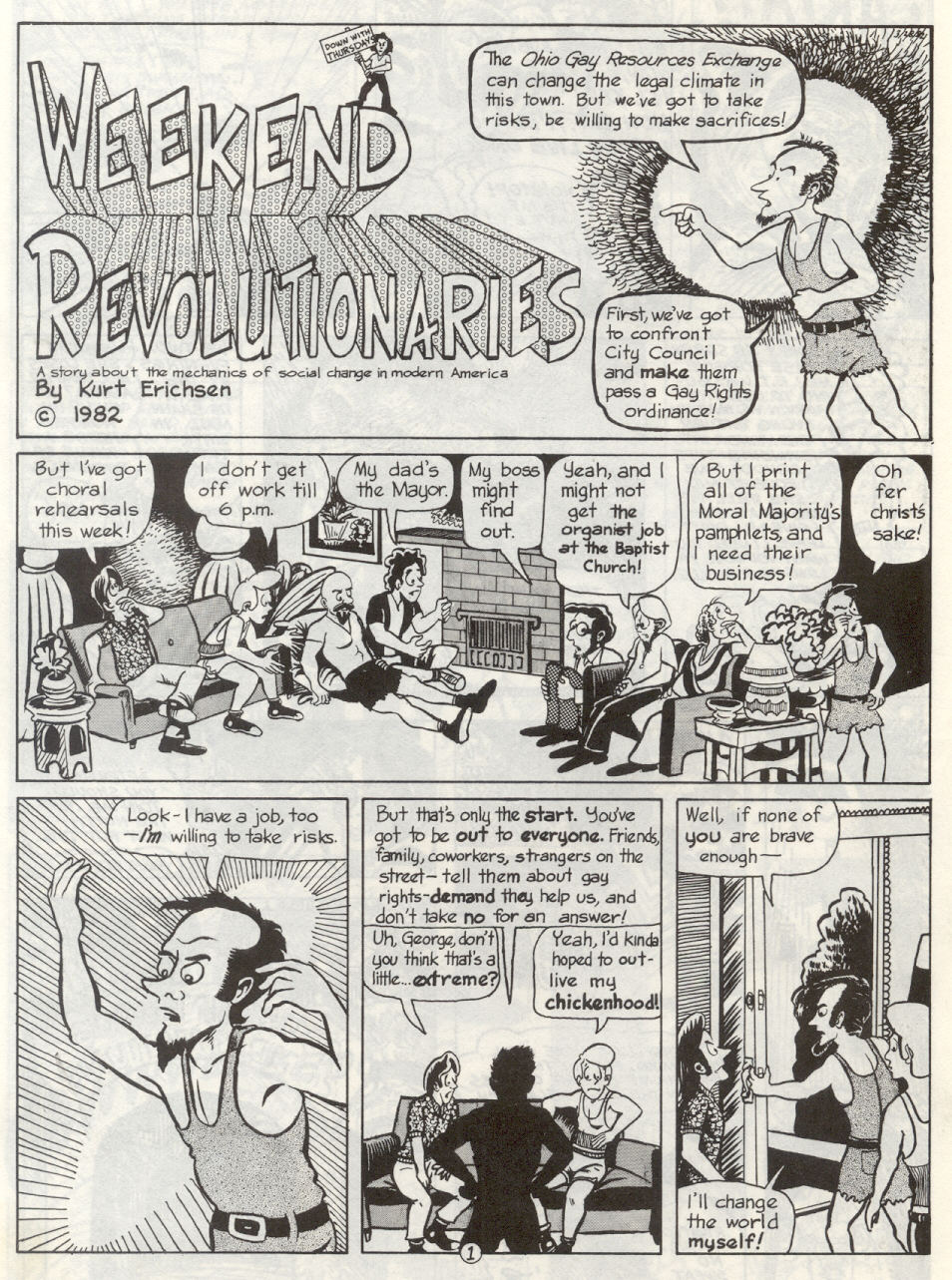

The (possibly, likely) unintentional theme of discord was found in some of the issue’s stories too, most notably in Kurt Erichsen’s “Weekend Revolutionaries”. Subtitled “A story about the mechanics of change in modern America”, the strip has a fittingly rebellious air, with a politically engaged community organiser, George, trying to garner support for a protest of the city council. While he wants to push for a local gay rights ordinance, he’s met with indifference and complacency from his gay friends.

It’s a snapshot of the time in that the battle for LGBTQ+ rights and recognition was so “small” – city level, not even US state rights – but the strip also touches on some issues that are contentious even today, such as the argument that “you’ve got to be out to everyone”. The standout comment from here in the future though is George’s angry assertion that the reason his friends are such “cowards” is that “there’s no danger in being gay anymore.” It’s wild to imagine that 40 years ago, long before many of the equality laws that have been hard fought for in the decades since, there was a segment of the gay male community (and it’s worth noting that George and his friends are all white – make of that what you will) that was just comfortable enough to not want to rock the proverbial boat. While the story takes a darker, criminal twist that touches on police violence and subjugation of queer spaces in America, it still lands the ending with a couple of dark jokes and some well-deserved comeuppance for the increasingly radical George, and leaves the reader with plenty to think about.

There’s more conflict and community explored in Cheela Smith’s “As the World Grinds to a Halt”. Framed as a soap opera on TV, albeit a far more progressive one than any that aired in the 1980s, it follows a lesbian woman named Jackie after being fired by her boss Dorian for refusing to sleep with her. Despite touching on themes of sexual harassment and coercion, it’s ultimately a light-hearted tale that proceeds in suitably exaggerated and soapish sweeps. While Jackie’s firing makes the local news, leading the lesbian community to hold a rally to support her, Dorian’s business hits the skids, delivering some delicious schadenfreude. It’s another example of the importance of queer community, and a more positive one than in Erichsen’s story.

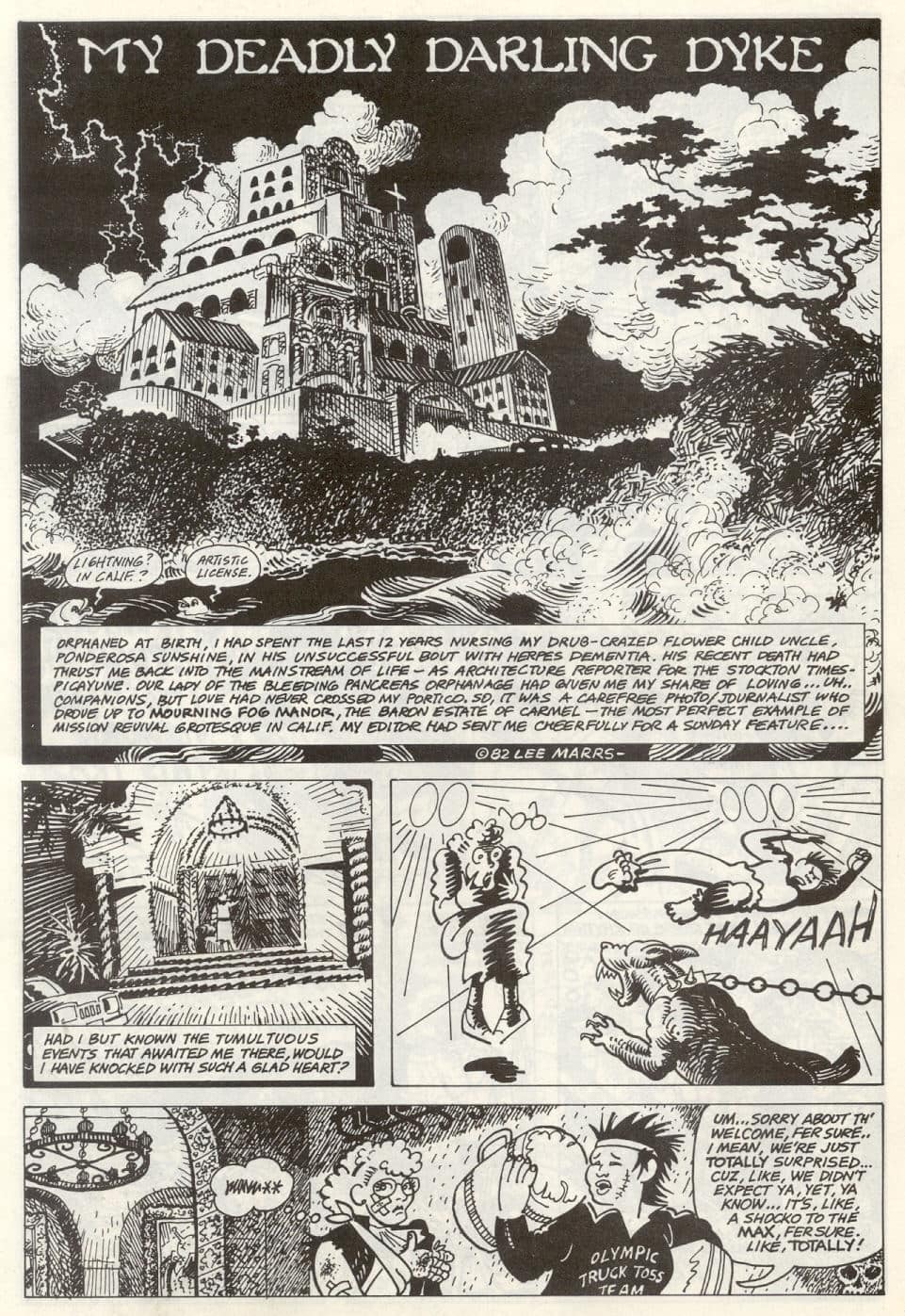

It’s the issue’s opening tale, “My Deadly Darling Dyke” by Lee Marrs, that offers perhaps the smartest twist on “conflict”, offering a dark but comedic take on power dynamics and authority, all with a side of lesbian BDSM. That’s more literally dark than thematically though – the comedic strip is almost entirely set at night, with a shy photo-journalist visiting the eerie Mourning Fog Manor to chronicle the life and times of its secretive owner, Lariat Baron.

The five pager introduces Lariat as a clear dominatrix archetype, wielding a riding crop in her first panel, and shortly after drawing the innocent journalist into a sado-masochistic relationship while introducing her to various fetishes and kinks. Despite the journalist – referred to only as Ms Timid – immediately falling for Lariat and all too easily going along with the sexual power play, she ignores Lariat’s one rule: to stay away from the manor’s bell tower, and to never mention Lariat’s missing former lover, leading to murderous consequences.

A clear send-up of gothic romances and with hint of Dracula for flavour, “My Deadly Darling Dyke” plays out as a loving pastiche, with added comedy from Lariat’s answer to Dracula’s Renfield – a muscle-bound Valley Girl named Emiko who does her every bidding (but only for a very reasonable salary package). There are some jokes and references to, seemingly, obscure Californian property law rulings that lack resonance now, but the strip remains an engaging and amusing reflection on power in relationships.

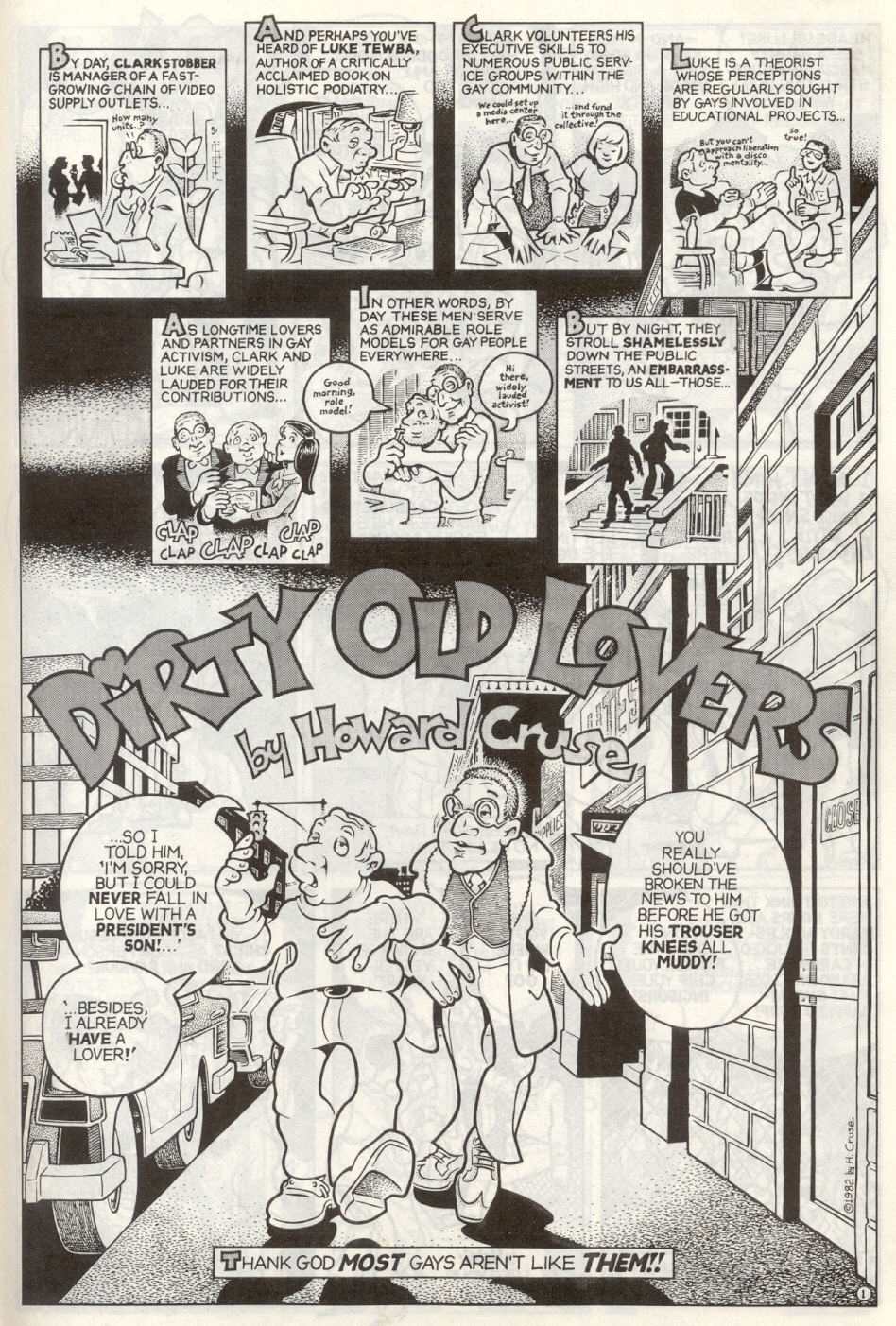

Editor Cruse pulls double duty on this issue, with the two-page “I Always Cry at Movies” offering a look at how cinema can evoke emotions that we struggle to realise in our real lives, while the longer “Dirty Old Lovers” explores similar themes around the gay community to Erichsen’s strip. Or rather, he eventually explores them – the majority of the five page strip follows elderly gay couple Clark and Luke, socially acceptable homosexuals by day, who transform into lecherous queens prowling the gay scene by night.

They’re far from predatory though: more likely to wax lyrical over the beauty of a passing young gentleman or quote poetry than they are to make a pass at anyone, although both able to disarm any would-be troublemakers with a flick of their wicked tongues. It’s a strip that could almost have been a test run for the Ian McKellen and Derek Jacobi series Vicious, which similarly followed a late-in-life gay couple.

It’s only on the final page where Cruse drops his satire bomb. Cruse makes it abundantly clear that he’s not only attacking the straight world that will only accept Clark and Luke so long as they are exemplary members of their community, paragons of virtue beyond reproach, and utterly non-sexual, but also the ‘respectability politics’ that was being demanded at the time by elements of aspects of the gay world. When the pair go to a very masc bar with Luke wearing a dress, they’re met with derision for being too effeminate, a scene that’s a clear condemnation of calls to sand off the rough edges of gay identities to better assimilate into mainstream society. There’s even a final panel that could fit right into 2022 and the torturously unending debates around “cancel culture”.

Gay Comix #3 isn’t all satire and dark humour though – it also delves into some emotionally tougher material. “One For Sorrow” by Patrick Marcel is a two-page reflection on the pain of realising you’re more invested in a relationship than your partner, comparing losing them to losing a limb. It’s a simple near-parable, told with anthropomorphic characters – Marcel’s artwork is evocative of Dave Sim’s Cerebus – but is resonant despite its brevity.

The most serious strip in the collection is undoubtedly Roberta Gregory’s “Another Coming Out Story” which, despite the title, isn’t really about coming out. Instead, it follows a young woman named Sara and her life-long relationship with alcohol. Coming from a family where booze flows all too freely, she initially doesn’t want to drink at all, but feels compelled to by the time she starts going to lesbian bars.

Over the years, Sara’s alcohol dependence grows, souring her relationships with girlfriends, and eventually proving a gateway to drug abuse and other self-destructive behaviour. It’s not an easy comic to read, especially in how it frames the toxicity of drinking culture and its often central role in queer communities, but it’s an important one. It also offers no easy answers – while Sara eventually attends Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, Gregory is savage in her attacks on the hypocrisy of them and how they often merely swap addiction to a substance for addiction to a framework. The closest the strip comes to optimism is Sara admitting that she hasn’t quit drinking, but she is willing to give quitting a proper try for the first time.

As a contrast to the issue’s more combative entries, “The Tale of Cha-Lee and Sat-Yah” by Demian proves the antithesis of its pagemates. Illustrated in Demian’s signature dotwork style, the four-page story is a glorious fable telling of two young boys who were soulmates from birth. Separated when Sat-Yah is forced to marry a woman, Cha-Lee sets out on an odyssey, only to find his beloved waiting for him on distant shores. There’s a dreamlike, mythic quality to the story, visually and narratively, which coupled with the sense of hope it conveys, makes it linger with the reader.

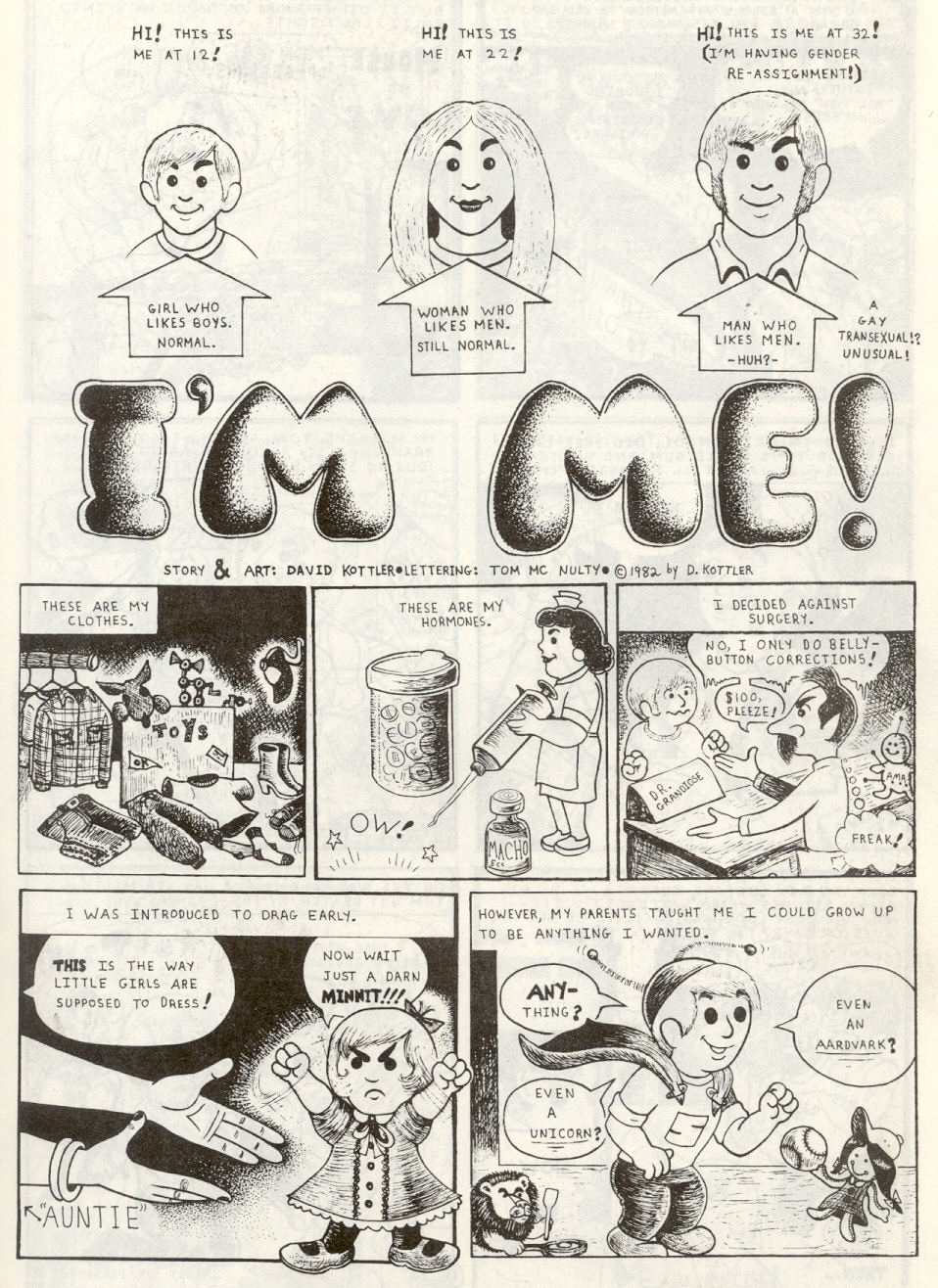

The greatest delight of the issue has to be David Kottler’s “I’m Me!” though. It’s the first strip in Gay Comix to feature explicitly trans characters, and does so in an endearingly positive manner. An autobiographical strip based on Kottler’s own transition, it explores his journey from childhood and struggle to fit in, lacking even the language to describe how he felt.

While some of the language is now outdated (“transsexual” rather than transgender is used, for instance), “I’m Me!” is rather timeless, showing trans people have always existed – a welcome reminder amidst contemporary culture wars. Even 40 years ago, Kottler openly discusses aspects of trans experience such as taking hormones, and explores the concept of feeling out of place in a world of binary genders. Best of all is the presence of Tom, David’s husband who devotedly supports and loves him through the ongoing experience of transition. It’s both beautiful and normalising; a welcome lesson from the past.

While Gay Comix #3 was the biggest issue to date – 44 pages, to the previous two’s 36 each – the quality doesn’t match the quantity. Some strips feel very much like padding, and have essentially no LGBTQ+ content. While gay creators are obviously not beholden to create gay material, entries such as Billy Fugate’s “Necropolitan Life”, where a mummified James Dean lookalike makes ghoulish puns over two pages, reads more like an homage to the “horror host” comics published by EC before the dawn of the Comics Code Authority than anything befitting a collection such as this. There’s a terrible joke about protein and bones, but it would be an incredible stretch to consider that even a gay reference. Elsewhere, single page strips – “My Most Embarrassing Childhood Experience” by Theo Bogart, two “Castroids” gag pages by Robert Triptow, and “Watch Out!” by Vaughn Frick – bring some gay humour, but feel supplementary rather than essential.

Taken as a whole, this issue of Gay Comix captured the increasingly vocal arguments within the real world gay community in the early 1980s, exposing some of the disharmony that was beginning to bubble under the surface as the gay rights movements became bigger and more complicated. As ever, the series remains a fascinating time capsule of queer creativity, and it’s remarkable how relevant many of its stories remain even now.

This article was originally published on our sister site, Gayming Magazine.