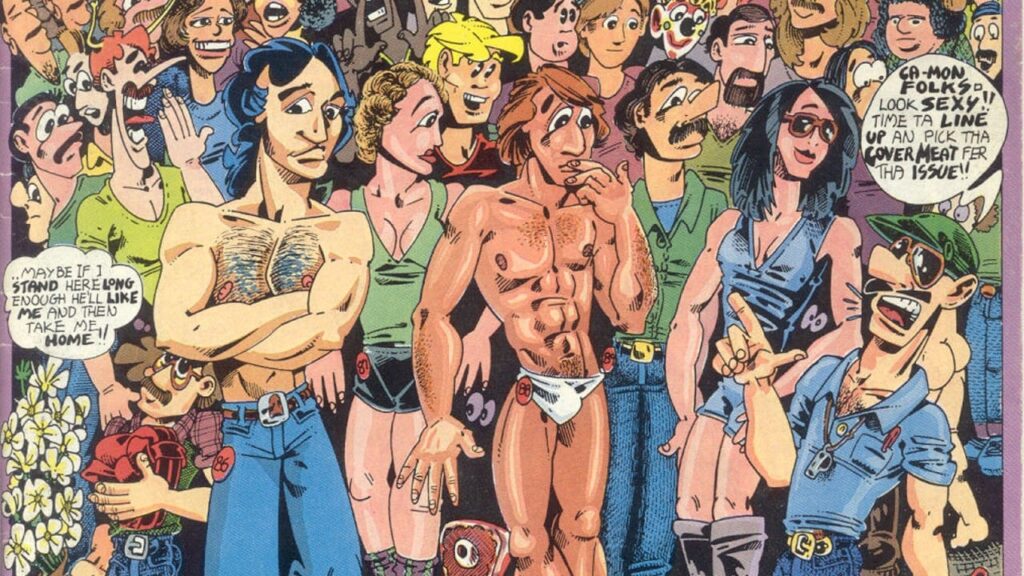

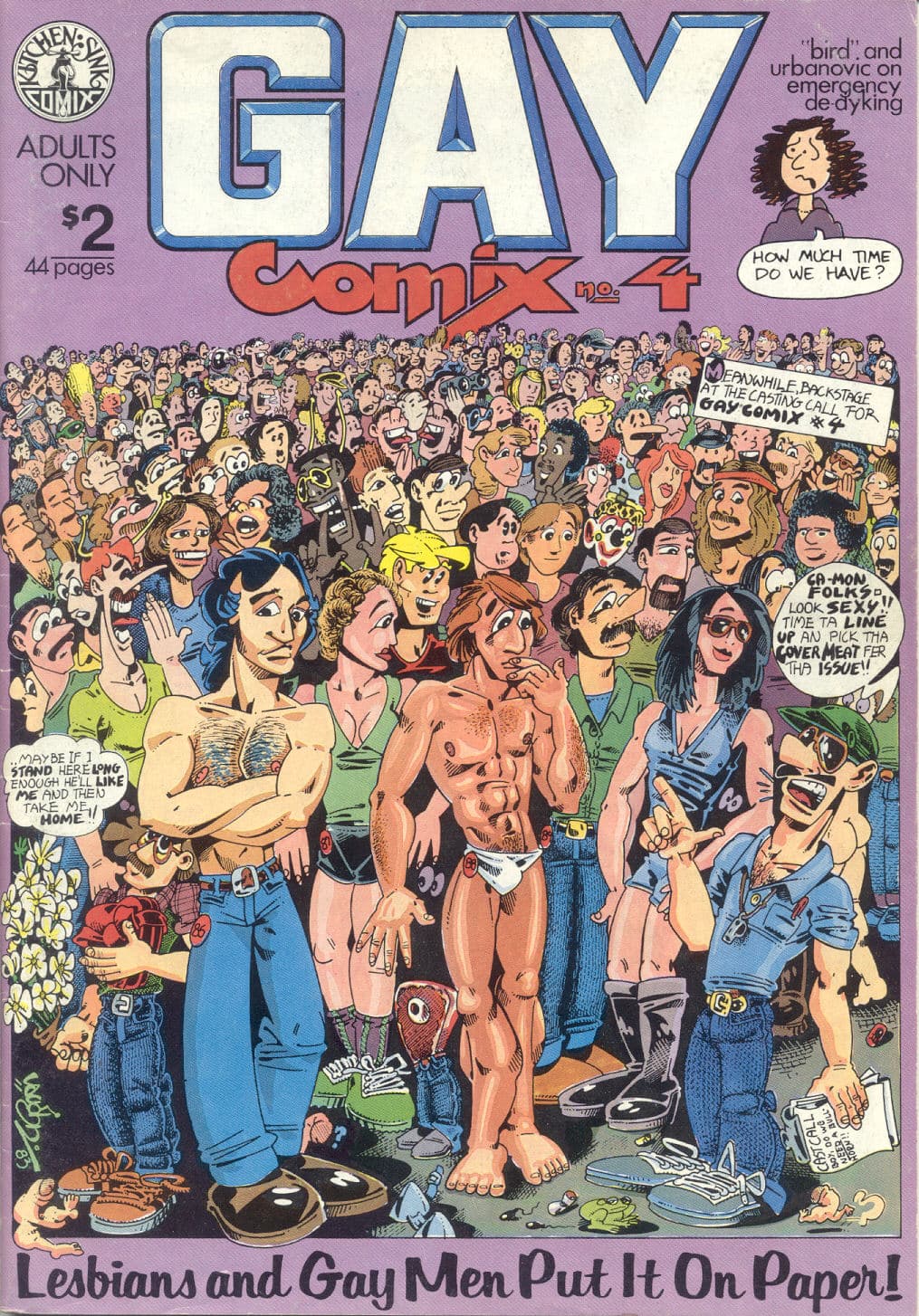

Comics Corner – The Historic Importance of ‘Gay Comix’, Part 4

It is November 1983, and the wider queer community is being savaged by the spread of HIV/AIDS. No wonder, then, that the then-latest issue of Gay Comix, the seminal underground comic that provided a voice and outlet for LGBTQ+ creators and readers alike, was perhaps the darkest yet, with a plethora of stories rooted in fears of social ostracisation, condemnation, and isolation. Yet through the darkness, moments of levity and hope shone through.

This is the latest in a series of retrospectives looking at the pivotal underground publication Gay Comix. You can find #1 here, #2 here, and #3 here.

If there’s a unifying theme to Gay Comix #4, it’s The Closet – that notorious metaphor for the shame and imprisonment queer people often feel, and from which we derive the term “coming out”. In the early 1980s, whether to burst forth from The Closet and live an authentic life or remain in hiding was an even tougher decision to make. While the growing visibility of openly gay people, particularly in major cities, was making in-roads in the wider public consciousness, fostering acceptance by showing the essential humanity of the community, queer people were also being met by a wave of hatred and condemnation, largely by those using the still-largely unknown virus to attack that same community. After all, it was only a year earlier, in September 1982, when the American Center for Disease Control had adopted the term AIDS to refer to the disease, having previously used GRID – Gay Related Immune Deficiency. To be out of The Closet meant to be identifiable as gay; to be identifiable as gay meant to be make a target of yourself to those who feared the so-called “gay plague”.

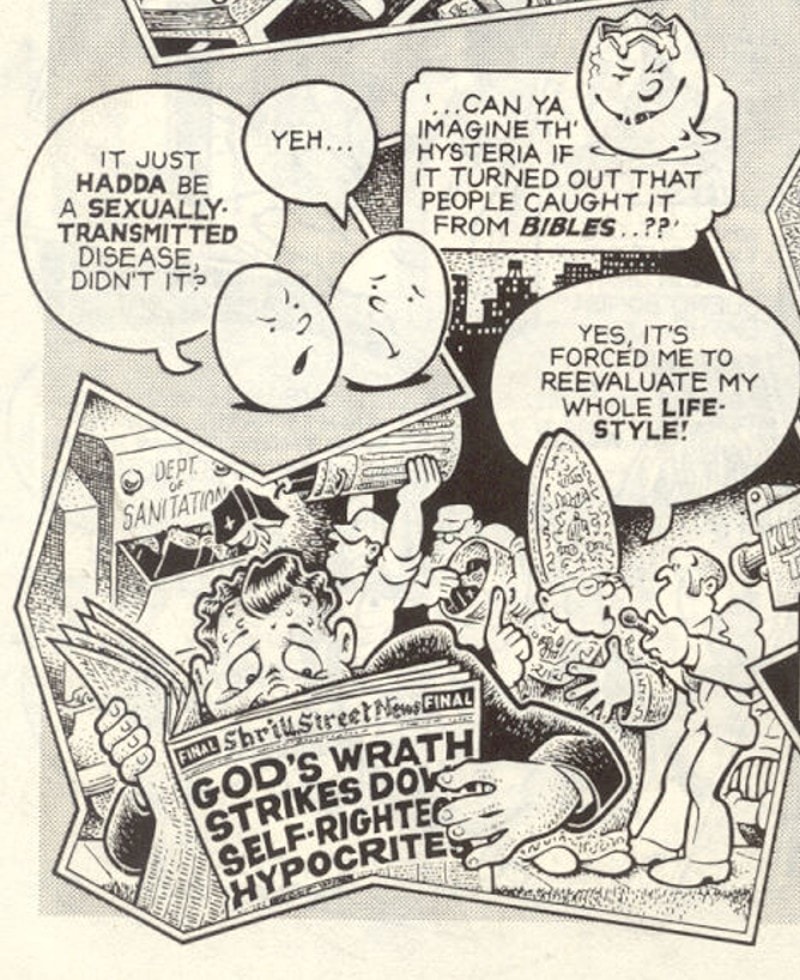

That sense of fear and confusion is most apparent in editor Howard Cruse’s own entry for the issue, “Safe Sex”. It’s one of Cruse’s most abstract and non-linear strips, more a collection of ideas, commentary, visual metaphors, and almost dreamlike imagery than a coherent story. It’s certainly a departure from his semi-autobiographical work in earlier issues, such as issue #2’s “Jerry Mack”. Instead, Cruse offers snapshots of the era, an invaluable if often satirical time capsule for us here in the 21st century.

Ironically, or perhaps deliberately, there’s no real discussion of safe sex in “Safe Sex”, bar a fisting-with-a-condom gag. Instead, Cruse is mostly vociferously decrying the Evangelical bigots who used the crisis of a disease that can be sexually transmitted to lambast the entire gay community. In one particularly savage panel, Cruse imagines how the self-professed saviours of souls would act if the illness were transmitted by Bibles, asking if the likes of priests would “reevaluate [their] whole lifestyle” as gay men were being asked to.

A wider society all too eager to absorb those attacks isn’t spared Cruse’s wrath. He attacks the racism of the public response to AIDS, highlighting how travellers from Haiti were effectively “presumed sick until proven well”, while an allusion to the deaths of closeted celebrities highlights how polite society would talk around the wider health crisis.

Every panel and caption of “Safe Sex” is a reminder of how confusing and scary the period was, though. Couples discuss forced monogamy or enter into contractual negotiations of what’s permissible before going on dates, while a gay son is handed dinner by a mother wearing a face mask and rubber gloves. Elsewhere, the mere idea of sex ignoring medical advice is rendered as a back alley exchange, with “bodily fluids” in place of drugs, while the whole community gossips about who has what and where they heard about it. It’s all filtered through Cruse’s inimitably wry sense of observationist humour, but every image still lands with a punch.

Cruse also hops between lamenting the gay men so starved of information and understanding of how HIV/AIDS was spread that they were consumed by “fear of the kiss that kills”, teasing those who were performatively lecturing others while still engaging in risky sexual behaviour themselves, and condeming the elements of the gay press that were haranguing their own readership for not behaving as sexless saints. And if that’s all too heavy, Cruse lightens things up with a joke about nuclear annihilation – it was the midst of the Cold War, remember!

Yet while Cruse’s work was the most overt in its discussion of the perils of the day in this issue, the same fears that were keeping people in The Closet were reflected in many other contributions to Gay Comix#4.

In Murphy’s Manor by Kurt Erichsen – a newspaper-style strip syndicated in other publications, with a selection reprinted over three pages here – the titular Murf pokes fun at the idea of a “positive gay image” (an assimilationist turn of phrase that was gaining traction at the time), while discussion of Pride parades turns into a gag about how people would travel to different cities to march, to avoid being seen in their home towns. Many readers of the time would have felt very seen by that jab.

“Walls”, by Rick Campbell, offers a more powerful interpretation of The Closet, going so far to present it as a prison that queer people build for themselves. The six page strip follows a young man named Joey, who knew he was gay from a young age, but wilfully maintained the illusion of heterosexuality out of fear of familial abandonment or social alienation. It’s a short but brilliant examination of how easy it is for closeted men to slip into patterns of toxic masculinity, cat-calling and objectifying women as part of their masquerade, even while experimenting with men in secret.

Campbell shows how each one of those lies adds a layer of bricks to the wall of the prison, peaking when Joey stands by and watches homophobic friends assault Jon, an openly gay student at his high school. Even after he musters the courage to apologise, going so far as to tell Jon he’s gay himself, Joey still runs back to his abusive friends, wondering if he “was actually walling out my enemies, or just building a permanent prison for myself?” It’s a question that haunts him through to university, where Joey – and the reader – are left with the possibility of change and personal acceptance, if not absolution for his earlier behaviour.

Joe Sinardi’s “Ode to Phyllis Anne” is less obviously about the perils of The Closet, instead focusing more on nascent feelings and unrequited crushes, but still capturing that sense of needing to hide one’s truth. The strip follows Jay, a teenager elated to be asked to the movies by his friend Mitch… only to be crushed when Mitch wants him to come as part of a double date, an attempt to set him up with the eponymous Phyllis Anne.

Phyllis Anne herself is never seen, but the weight of expectations surrounding her is felt by Jay. Mitch, oblivious but ostensibly well-meaning, offers advice on how Jay can better woo her, never picking up on his friend’s discomfort at being forced into asking her out and taking her on a date. There’s an innocence throughout the story too, with Jay’s own journal entries interspersing the panels, his innermost thoughts indicating that not even he truly realises how he feels about Mitch – at least not yet.

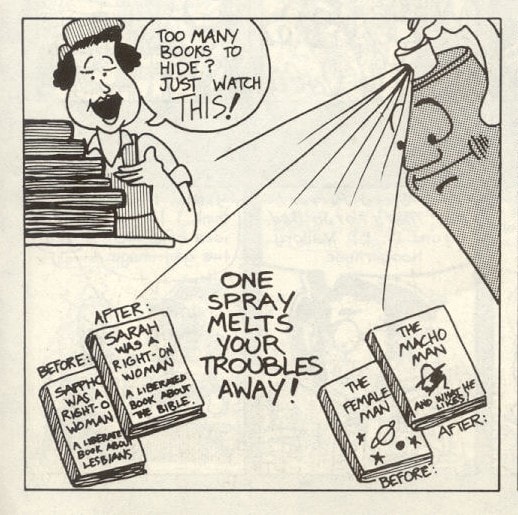

Even some of the lighter, more purely comedic strips in this issue touch on the idea of queer people living in hiding. “A Word From Our Sponsor…”, by Jackie Urbanovic and ‘Bird’, is a hilarious two-pager framed as an advert parody, where two lesbians try to hide anything obviously gay from their home before a visit from a disapproving aunt. It’s a task made easier with the hot new product De-DYKE, “the feminine spray no home should be without!”, that promises to magically turn books about Sappho into Bibles and hetero-fy lesbian posters. A real-life version would have probably sold well in 1983.

“Billie”, by Jim Yost shifts focus slightly, offering a one-page condemnation of the lack of solidarity various gay ‘tribes’ offer each other. The title figure presents themselves as “the essence of gay sensibility”, whose “androgyny is complete”, and speaks in honeyed words of how they escaped a hateful biological family to find a new chosen family in the wider community – only for a passing ‘masc’ gay couple to condemn Billie as a “nellie fem” who “give[s] gay a bad name”.

Yost also penned “Scrapbook” in the same issue, a tale of heartbreak and abandonment told in monologue form, where a jilted lover laments the beautiful man who left him, thinking he was too good for him anymore. Painted in shadowy, inky tones, it’s a painful, almost morose short for anyone who’s suffered a break-up, made all the more upsetting by the ending line: “I miss him”.

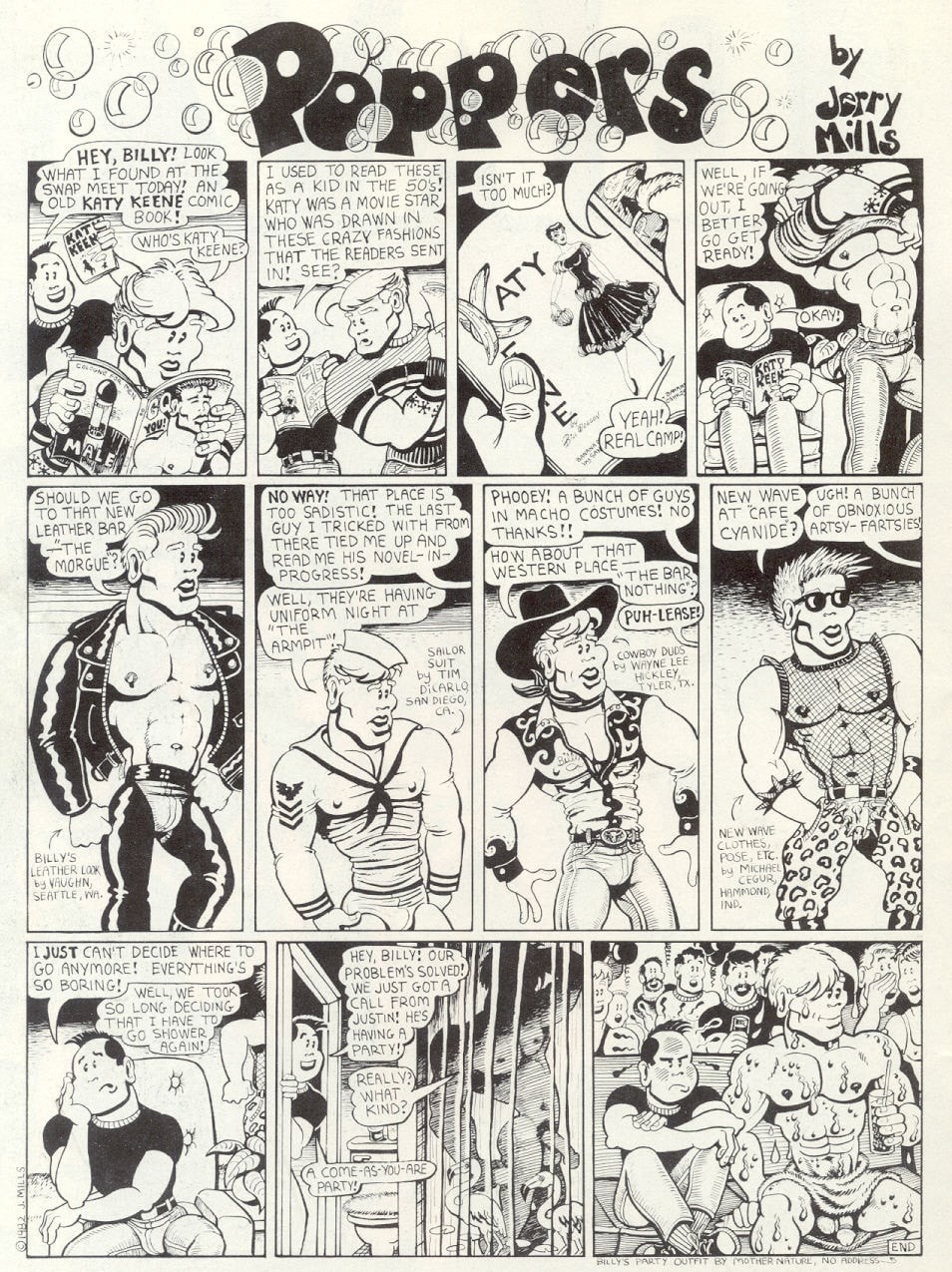

Heavy stuff throughout, but more of that aforementioned levity is found in the works of creators such as Jerry Mills, Lee Marrs, Vaughn, and Jennifer Camper. Mills opens the issue with his one-page comedy strip “Poppers” – like “Murphy’s Manor”, more regularly published in other titles, and reproduced here – which offers a wonderfully tongue-in-cheek take on the classic romance/fashion comic Katy Keene, while Marrs’ “Networking” is almost a comedy of miscommunication, as a new employee at a record label struggles to recall her colleagues soap-operatic connections, until one of them proves a dating opportunity. Vaughn takes readers on an out-of-this-world adventure into sci-fi farce, with “Stan Stone: The Little Writer Nobody Loves”, where a self-deprecating man, too shy to even pee in a gay bar’s restroom, is abducted as the love slave of the gaylien Cozmic Clonez – intergalactic stereotypes and scene queens, who won’t take no for an answer. Camper, meanwhile, gets one of the bluntest, funniest punchlines in the single page “Ettiquette”, which probably shouldn’t be used as a guide on how to introduce parents to a same-sex lover.

The issue is rounded out by the then-latest work from Roberta Gregory, an artist who is as much a fixture of Gay Comix as Cruse. Gregory’s contribution to the issue is her strangest entry yet, the almost ethereal “The Unicorn Tapestry”. Starting out as a children’s fable, a simple allegory comparing the rarity of unicorns to visible gay people – “just because something is rare, it doesn’t mean that it’s always treated as special” – it morphs into an almost hallucinatory analogy for trans identities and gender dysphoria, veers into bleak territory with a character’s suicide attempt, dabbles with the historic role of gender nonconforming people as tribal seers and storytellers, and rounds off with a wholesome family moment.

Of all Gregory’s work, “The Unicorn Tapestry” is perhaps the closest to being a pure, stream-of-consciousness string of ideas. Nearly four decades removed, it could be said that the language possibly didn’t quite exist to fully explore some of those ideas, which may account for the strip’s disparate, uneven nature, but it still proves strangely thought provoking; like a dream where you can’t quite shake the imagery after waking.

This fourth issue of Gay Comix also marked the end of an era – it was the last issue Howard Cruse would edit. Having guided the series since launch in 1980, he stepped away from the role with this issue, although would continue to contribute to the series creatively in future. This proved a strong issue to bow out on though – the most political and increasingly socially aware issue to date, with stories that resonate still.