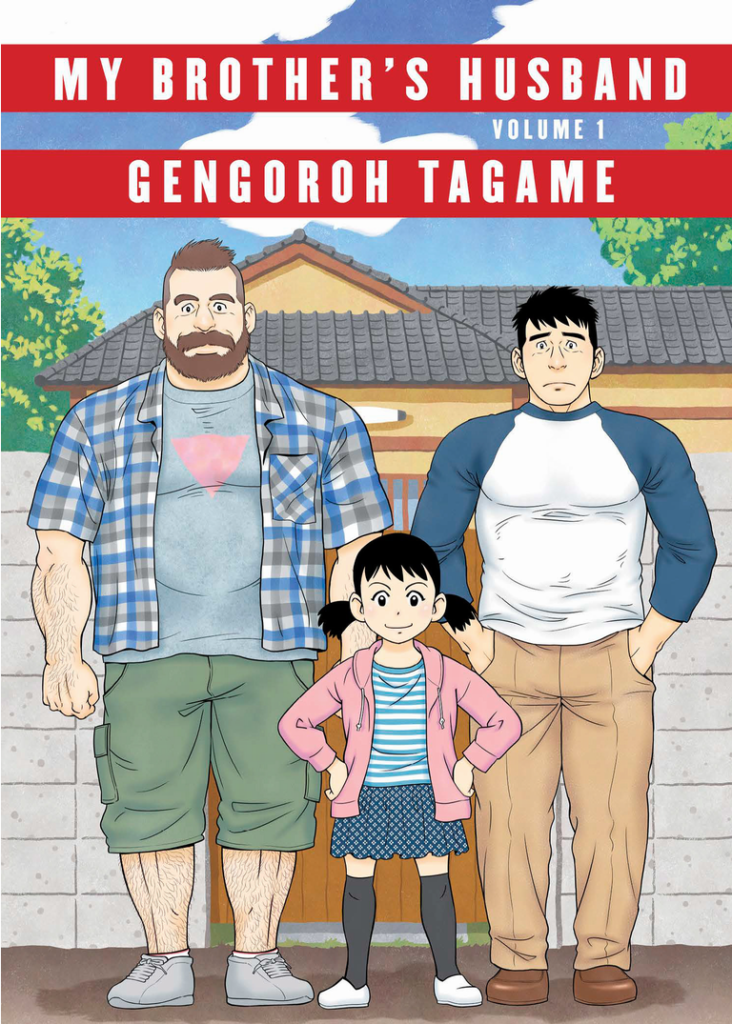

Comics Corner – My Brother’s Husband is gay manga at its heartfelt best

Family dynamics can be complicated for LGBTQ+ people – but in My Brother’s Husband, a culture clash gets thrown into the mix as well, as a gay Canadian comes to visit his late husband’s Japanese family. Relax though: what could have been horribly awkward is instead a sweet, charming, and heartfelt dose of slice-of-life storytelling, and one you should absolutely seek out.

The series is the work of Gengoroh Tagame, one of Japan’s most noted gay manga artists. While Tagame’s background is in often-explicit bara manga – comics for a gay male audience, unlike yaoi, which is usually created by and for straight women, despite typically featuring male same-sex pairings – My Brother’s Husband was his first all-ages title.

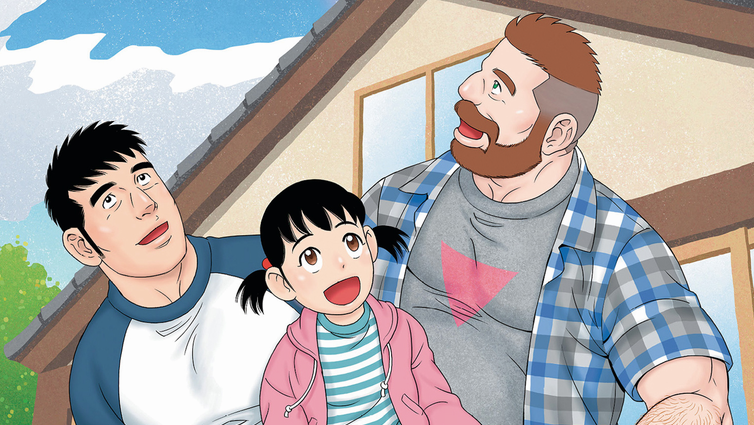

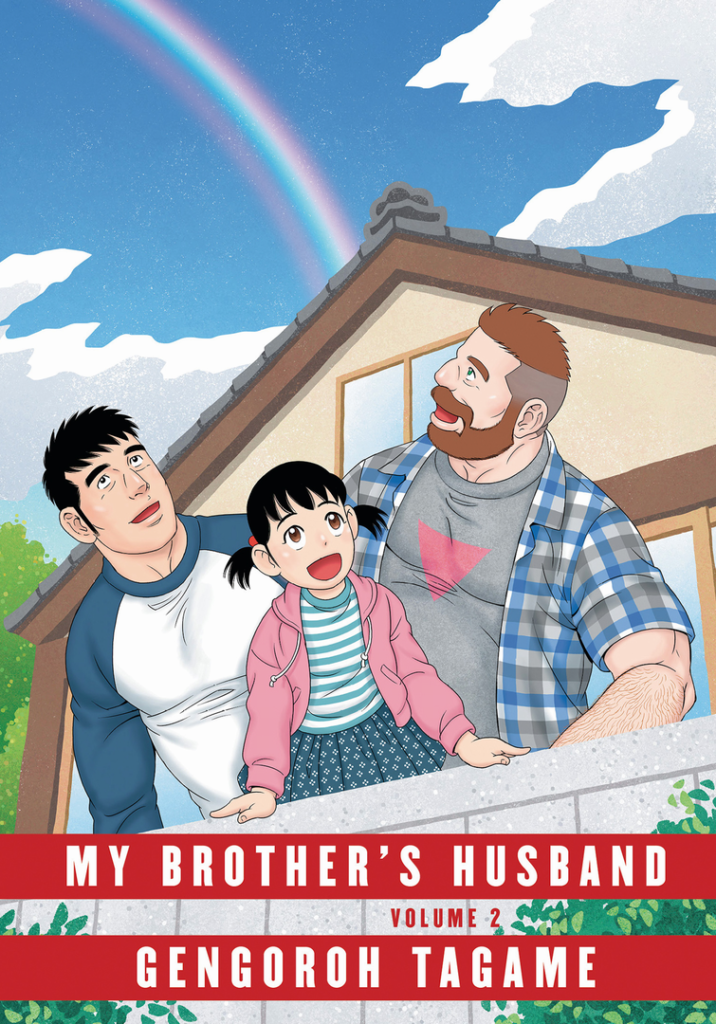

The focus is tight, introducing readers to single father Yaichi and his young daughter Kana, whose world is changed by the arrival of Mike Flanagan – widower of Yaichi’s estranged brother Ryoji. While Mike seeks to connect with his late husband’s family and learn more of his past, his arrival forces Ryoji to re-evaluate his own perceptions of homosexuality, and his relationship with his departed twin.

While Ryoji initially struggles with Mike’s presence, Kana immediately warms to Mike, thrilled by her exciting new gaijin uncle and easily accepting of his being gay. It’s through Kana’s innocence that Yaichi begins to understand that his own discomfort with gay people, including not knowing how to deal with his brother’s coming out, is unfounded. As word begins to spread of the large gay westerner staying with him and his daughter, elliciting homophobia from some and curiosity or even empathy from others, Ryoji begins to think more deeply on Japan’s cultural biases towards LGBTQ+ people.

Many of the chapters are adorable anecdotes of Mike experiencing the delights of day-to-day Japanese life while building a relationship with his niece. However, there are deeper and more serious themes at work throughout – My Brother’s Husband is fundamentally a story of loss.

Yaichi’s life in particular is marked by tragedy. First, with him and Ryoji suffering the loss of their parents at a young age, then the metaphorical loss of his brother when he moved to Canada. This is compounded by his divorce from Kana’s mother – although the pair seem to have a friendly relationship now – and drawn into stark focus as both he and Mike deal with Ryoji’s passing in different ways. There’s a particularly poignant moment as Yaichi realised Mike knew Ryoji better than he did, at the end.

Mike, meanwhile, is fascinating, especially as a depiction of someone from a western country. Although a self-described otaku himself, he’s also a tall, bearded, hairy white man – the kind of “bear” that Tagame frequently drew in his explicit work – whose sheer physicality is a shock to most of the Japanese characters he meets. However, his kindness tends to win people over – effectively telling Japanese readers “hey, gays aren’t scary!”

Mike is emotionally complicated too. He often struggles being around Yaichi, a man identical to his husband, and at one point breaks down crying, drunkenly mistaking Yaichi for Ryoji. The growing relationship between the brothers-in-law is one of the key pillars of the book.

Ultimately, Mike is Tagame’s lens to shine a light on Japan’s conservatism, not only in regards to LGBTQ+ rights but also subtler ways, such as hugging people – even family members – generally being culturally unusual. At times, he’s sort of a “Gayness 101” primer, but that feels important for any audiences who need that basic education. A nice but subtle touch that may be lost in translation is that Mike’s dialogue is usually very simple – a way of showing that he’s speaking faltering, imperfect Japanese.

It would be remiss not to praise Tagame’s art as well as his storytelling. His style is clean yet detailed, capable of conveying a wealth of emotion in a single panel. His characters are beautifully distinct too, with even the young characters such as Kana and her friends conveying a world of personality in their fashion and body language on the page. Tagame also brilliantly – and often hilariously – uses panel breaks to jump from imagination to reality, most commonly showcasing what the uptight Yaichi really thinks of a situation compared to how he actually reacts to it.

While My Brother’s Husband is indeed an all-ages appropriate read, there are reminders of the creator’s roots though. His appreciation of the male form is on full display, with both Yaichi and Mike being muscular and well-built, despite their very different physiques. Perhaps ironically though, bathing scenes that wouldn’t raise an eyebrow in Japan may be considered more risqué to western readers!

While the individual stories that make up each chapter of My Brother’s Husband are simple, they make for a complex and often emotionally challenging whole. It’s a work that challenges cultural and sexuality standards, and proves as educational for western readers who may criticise Japan’s slow movement on LGBTQ+ rights from afar, as much as it is for Japanese readers with outdated views on gay people’s very existence.

Its warmth and accessability has helped it become a tremendous success though. My Brother’s Husband has seen a live action TV adaptation in Japan, and the original manga has both attracted critical acclaim and seen Tagame pick up a slate of awards, including a prestigious Eisner Award in 2018. With the complete series available in English from Pantheon Books, it’s a title no reader should miss.