Comics Corner – Marvel vs DC: Coming Out Edition

While both Marvel and DC have become considerably more welcoming places for LGBTQ+ characters in recent years, that wasn’t always the case. In the 1980s, Marvel’s then-Editor in Chief, Jim Shooter, reportedly had a policy that there were “no gays in the Marvel Universe” (and in 1980 wrote a story in Hulk! Magazine where Bruce Banner, the alter-ego of the Hulk, almost gets raped by two men in a YMCA shower – the only gay presence at the publisher). DC, meanwhile, was at least outwardly less aggressively anti-gay but still spent decades dodging, for instance, the undeniable realities of Wonder Woman’s Amazon sistren living in an all-female society on Themyscira.

In the ’90s, things began to change at both publishers. As the gay rights movement in the real world gathered force, and gay and lesbian characters became more visible in television and film – though notably few other representatives of the LGBTQ+ community – the decade would see both Marvel and DC have existing characters officially come out.

For this week’s Comics Corner, we’re going to look back and compare pivotal coming out issues from both publishers, and leave it to you to decide whether Marvel or DC handled the delicate issue best.

We’ll start with Marvel, where the search for the company’s first outing takes us to Canada, and the ranks of Alpha Flight, a team of superheroes operated by the Canadian government. First appearing in the pages of Uncanny X-Men #120-121 in 1979 – trying to return Wolverine to his former handlers – the team proved popular enough to earn their own ongoing series in 1983. One of the members, Northstar – aka Jean-Paul Beaubier, a mutant who possesses the power of flight and speed, and to produce blinding light when in contact with his twin sister Aurora – had been intended by creator John Byrne to be gay all along but due to Shooter’s edict, was only coyly alluded to as such for most of the series’ run.

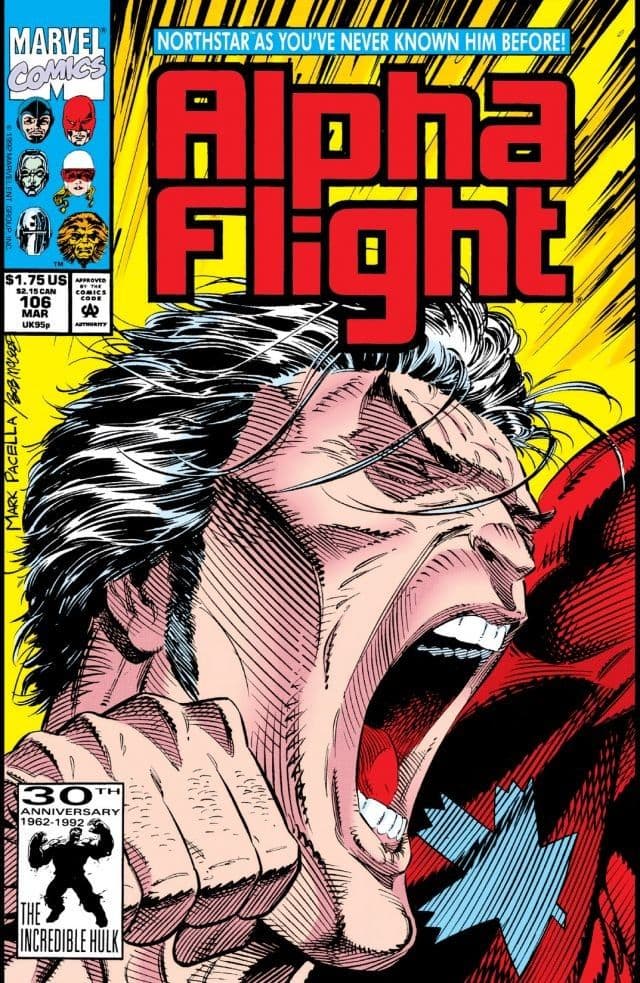

Fast forward to 1992. Alpha Flight had now run for over 100 issues, and was being written by Scott Lobdell with art by Tom Morgan. With Morgan reportedly running late, Lobdell turned to an “inventory” script – standalone stories that can be slotted into the production order in case of unexpected delays elsewhere. This lead to Alpha Flight #106, pencilled by Mark Pacella with inks by Dan Panosian, where Northstar would finally say the words “I am gay”.

The issue found Alpha Flight in battle against the American criminal Mr Hyde. Knocked aside by the villain, Northstar finds a baby girl abandoned in a garbage can. Taking her to hospital, he eventually learns that the infant has AIDS. Given the celebrity status of Alpha Flight as Canada’s national super-team, the media follows her progress, including Jean-Paul adopting her and naming her Joanne Beaubier.

The nonstop coverage proves to be the breaking point for an old man named Louis Sadler – formerly the hero known as Major Mapleleaf, created by Lobdell for the issue and retconned in as a World War II era ally of Captain America. Attacking the hospital in a delusional rage, he actually tries to kill the infant – because no one had cared when his son, Michael, had died of AIDS because he was gay. Northstar tackles the fallen hero Mapleleaf and, in the midst of a battle that smashes through several city blocks, reveals that he understands the travails of the gay community because he himself is gay.

News of the reveal leaked ahead of publication, with the issue selling out. Despite the hype though, Northstar’s actual coming out doesn’t even get a full-page impact spread – it’s a single widescreen panel taking up roughly one-third of a page. The lettering almost hides the actual phrase “I am gay” too, practically burying it in the bottom-right corner of the panel.

One could almost suppose Marvel had wanted readers to gloss over the declaration, if not for the fact that the rest of the issue loudly addressed some prominent issues for the gay community at the time. Besides the health crisis, the issue also touches on the importance of visibility and the problems of Northstar staying in the closet, and calls out political inaction on HIV and AIDS. Weirdly, the comic is capped with a pin-up of Northstar, Wolverine, and fellow Alpha Flight member Puck drinking beers though, so perhaps there was some effort to ensure the character was still perceived as masculine, despite coming out as gay.

While it’s perhaps troubling that Marvel’s first out gay character is revealed in an issue centred on AIDS, it is worth remembering that 1992 was the middle of the AIDS crisis – deaths were still rising year on year, and wouldn’t begin to fall until 1996 – which helps explain some of its bluntness. The issue was as much a public health sermon as it was an important character development, and on that front it at least packed in some surprisingly accurate information on the illness, such as how HIV can sometimes be transmitted to infants by their mother, or how even at the time it wasn’t solely a ‘gay disease’.

Unfortunately, Northstar’s sexuality would barely be mentioned for the remainder of Alpha Flight, which ended at #130 in 1996 – bar a subplot where his sister Aurora, who suffered from multiple personalities, did not accept his being openly gay in one of her identities. Fast-forward again to 2012 though, and Northstar’s sexuality was prominently and wholesomely presented – he married his husband Kyle Jinadu in Astonishing X-Men #51, in mainstream comics’ first same-sex wedding.

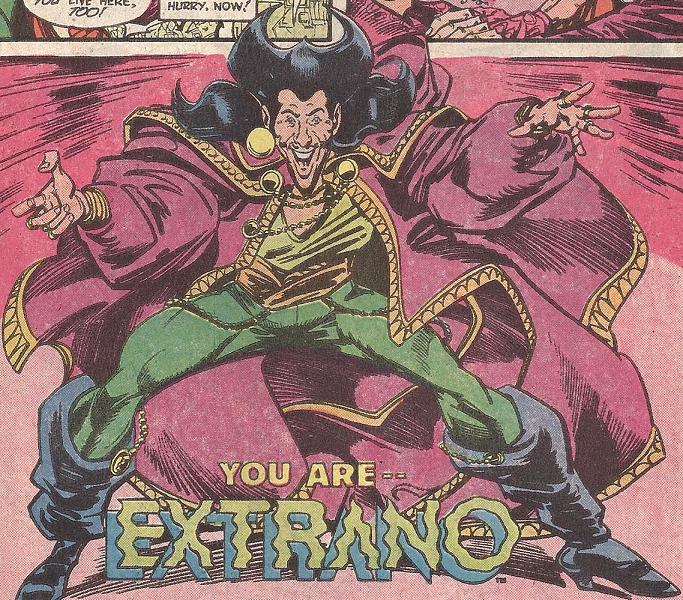

Over at DC, the criterion of who was the first out gay is a little trickier to define. Technically, DC’s first gay superhero was the extremely niche Extraño, who first appeared in 1987, spoke in high camp clichés and looked like, well, this:

However, despite being a walking collection of gay stereotypes – such as calling himself “Auntie” in the third-person – Extraño never outright said he was gay, nor did he ever have a boyfriend. So the honour of being the first openly gay DC character goes to Hartley Rathaway, AKA the Pied Piper – a reformed villain turned friend and ally of Wally West, the third Flash.

Look at the cover of 1991’s The Flash #53 (written by William Messner-Loebs, with art by Greg LaRocque and José Marzan, Jr.) and you wouldn’t think the Piper was even in the issue – it’s billed as a team-up issue with Superman. Indeed, crossing paths with the Man of Steel eats up most of the story, with Superman asking for Wally’s help in tracking down a kidnapped Jimmy Olsen. At the start of the issue though, Wally and Hartley are just hanging out, talking about their strange lives in the superhero world.

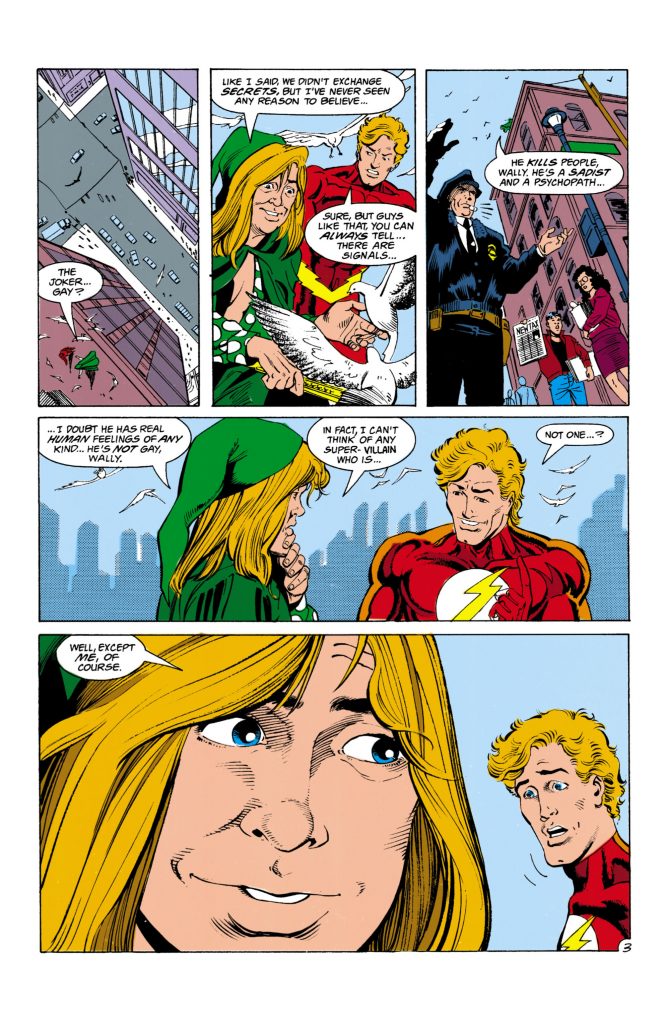

The conversation turns to gossip – specifically that the Joker is rumoured to be gay. For context, this issue came out a year before Harley Quinn would make her first appearance on Batman: The Animated Series, and eight years before she would be worked into the core DC continuity. A guy running around in a flamboyant purple suit who’s obsessed with a man who dresses up in black combat gear every night is going to get people talking.

Piper deflects at first, pointing out that even when he was a supervillain, he didn’t really know Joker, and that criminals didn’t “all live in a clubhouse of evil!”. As Flash blindly pushes the point though, saying that “with guys like that, you can always tell”, Piper reminds him that Joker isn’t gay – he’s a murderous psychopath, devoid of human emotion of any kind. Going further, he says he doesn’t know of a single supervillain who was gay… except him.

Wally, in response, panics and runs off. To his – and writer Messner-Loebs – credit, he’s shown to be angry at himself for having not noticed and for putting his super-fast foot in it, rather than being disgusted or worrying that Piper would hit on him (an all-too-common response from straight characters to anyone coming out). Piper is left behind, smirking at Flash’s faux pas.

As with Northstar’s outing, Piper’s is a done-in-one issue, but unlike in Alpha Flight, it’s not the focus of the story. The remainder of the issue is about Flash and Superman rescuing Jimmy Olsen – a situation resolved by having Piper pretend to be Flash to fool the villain of the day. It’s a softer, gentler approach, one that ultimately reinforces Wally and Hartley’s friendship at the end, rather than trying to sensationalise every facet of gay live in the 1990s.

Which approach handled it better though? Northstar’s coming out was undoubtedly the bigger splash, focusing on a character with ties to the X-Men, and his sexuality has remained an important part of the character’s later stories. However, the focus on AIDS in Marvel’s first story featuring an openly gay character was distasteful, even at the time. It was also arguably reactive, coming seven months after The Flash revealed Pied Piper was gay.

The merits of Piper’s outing, beyond coming first, are that it was more realistic – a quiet conversation between friends that, although awkward, didn’t affect their friendship – and didn’t shoehorn in heavier issues. The character’s gayness has even survived the transition to TV, with the Pied Piper a recurring character on the live action The Flash, played by openly bisexual actor Andy Mientus.

Conversely, DC’s first openly gay character is an incredibly niche one, and his actual coming out gets all of four pages of focus in the issue. It could be seen as the publisher wanting to hide the fact as much as possible, and only risked allowing a gay character at all if it was one it could bury if it had attracted bad publicity. There’s also the fact that it was a former villain, rather than a more marketable ‘classic’ superhero, who was selected, and while Piper would remain a friend and ally of the Flash throughout Wally’s tenure as the Scarlet Speedster, he’s also flitted back to villainy on occasion.

Ultimately, both of these stories were historic and important, paving the way for more and better LGBTQ+ representation at both publishers. Which do you think handled the matter best at the time though? Sound off in the comments below and let us know.