BearWatch: Queer filmmaker Graham Kolbeins discusses new documentary ‘Queer Japan’

Queer filmmaker Graham Kolbeins’ new documentary film Queer Japan gives us a valuable and eye-opening insight on Japan’s large and multifaceted queer community.

Japanese art has long been a major influence for many queer people. Highly stylized, beautiful, provocative and sometimes brutal, contemporary Japanese art, particularly manga and anime, is constantly innovating contemporary art and pushing boundaries beyond what is considered acceptable. It is no wonder why it resonates so much with those who oftentimes feel othered and misunderstood.

Homoerotic Japanese Manga has also seemed to grow in popularity in recent years, particularly with the bear and leather communities who appreciate the big, burly, beefy men in various sexual scenarios presented in works by such artists as Gengoroh Tagame and Jiraiya. All of these works highlight, not only how Japanese art influences queer and pop culture, but it also call on us to acknowledge and educate ourselves on the existence of queer culture in Japan.

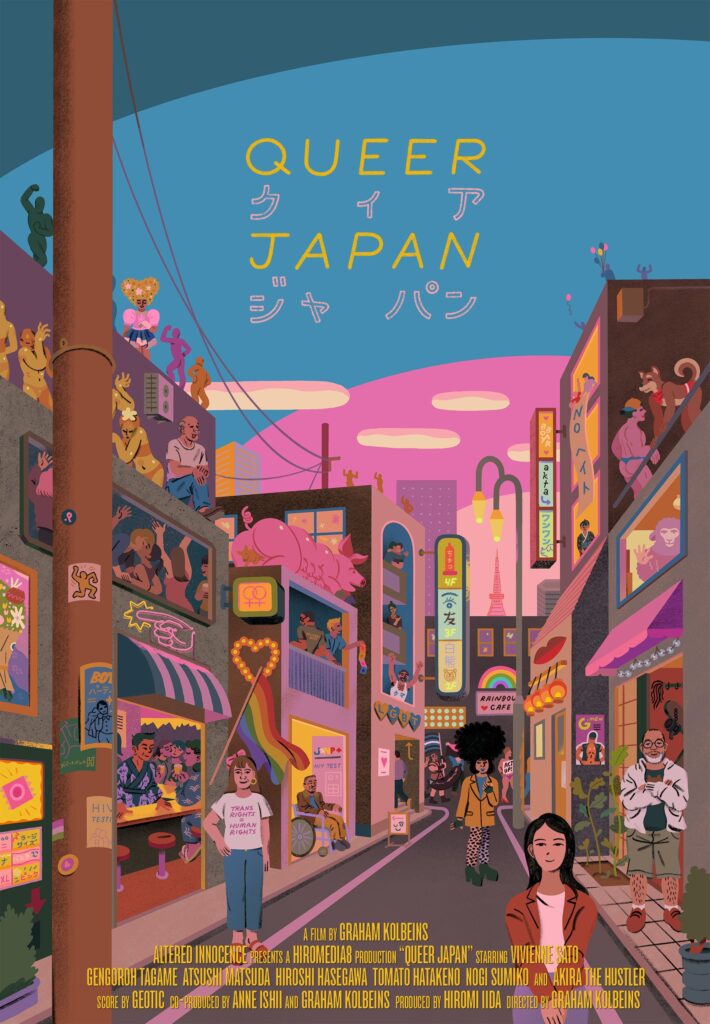

In the new documentary film Queer Japan, which is being released today, Canadian-American filmmaker Graham Kolbeins highlights the experiences of “trailblazing artists, activists, and everyday people from across the spectrum of gender and sexuality defy social norms and dare to shine in this kaleidoscopic view of LGBTQ+ culture in contemporary Japan.”

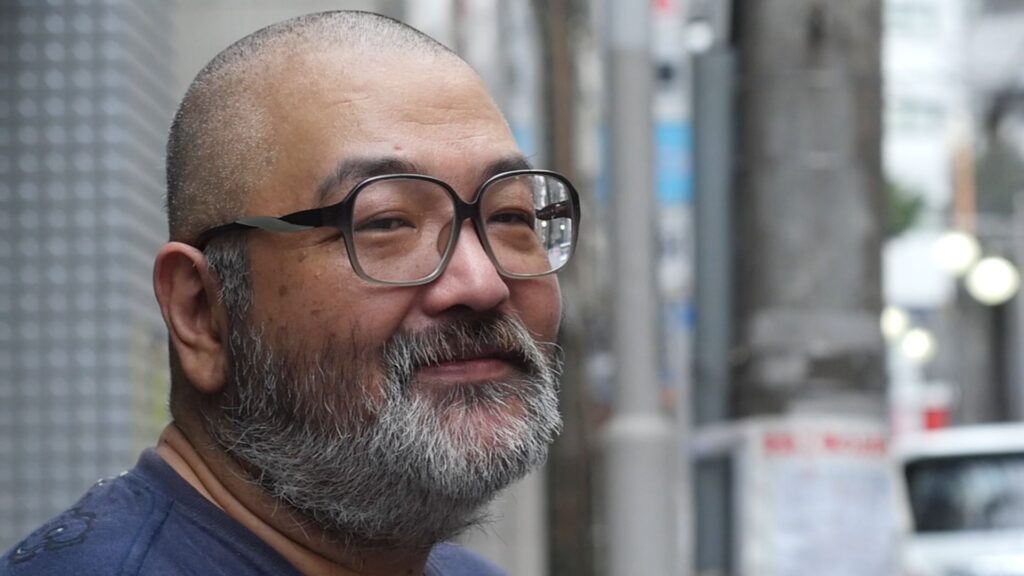

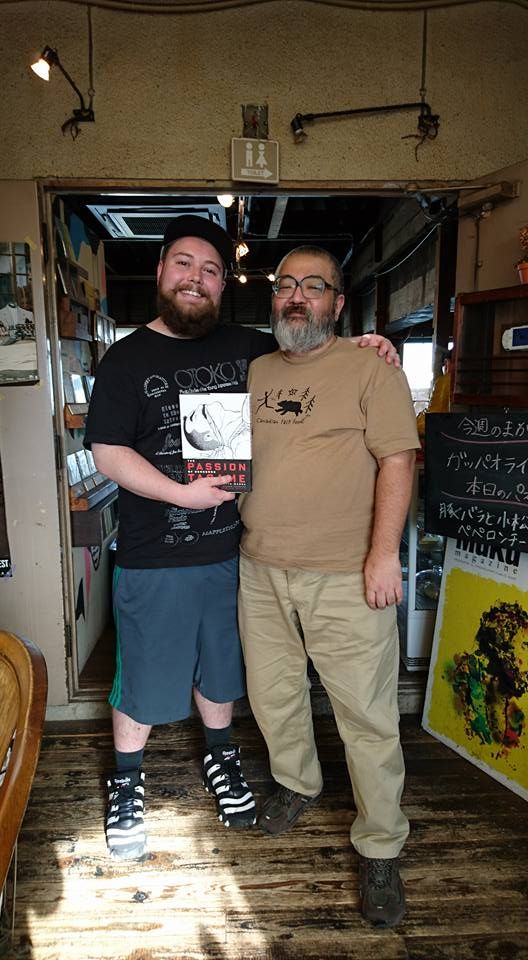

“I was starstruck in 2012, when I met [Gengoroh] Tagame in a Tokyo cat café, and thrilled to soak up as much knowledge as I could about his experiences as a trailblazing creator of gay culture in Japan,” says Kolbeins.

After our interview, Anne [Ishii] and I ventured into Tokyo’s gay neighborhood, Shinjuku Ni-chome, and found ourselves humbled by the sheer breadth and depth of the queer community. I had been drawn in through the relatively narrow frame of gay manga, but it was the multitudes of Japan’s queer culture that impressed me most. I fell in love with these vibrant, thriving LGBTQ+ communities that virtually did not exist on the radar of American culture.

Graham Kolbeins

Kolbeins’ experience in Tokyo was the catalyst for the creation of Queer Japan, which Kolbeins says “evolved organically”. And, while working on Queer Japan was a passion project, Graham makes it clear that they want the queer community of Japan to take center stage. ‘From the start, it was our goal to focus on our subjects’ lived experiences and center their voices to paint a multi-subjective portrait of queer life in Japan”, they state.

As a white cis male director aware of the long history of American colonization in Japan, it was especially important for me to remove myself from the frame as much as possible and avoid imposing any preconceived notions. I saw my role as a listener and an observer, a cheerleader for a community that deserves to be celebrated.

Graham Kolbeins

Some of the subjects for Queer Japan include: Dazzling, iconoclastic drag queen Vivienne Sato, maverick manga artist Gengoroh Tagame tours the world, transgender Councilwoman Aya Kamikawa recounts her rocky path to becoming the first transgender elected official in Japan, non-binary performance artist Saeborg, and legendary drag artist Simone Fukayuki.

I recently had a chat with Graham about creating Queer Japan and the meaning of “queer”.

Kyle Jackson: Hi Graham! So, can you tell me how you got started in film? What’s your background in filmmaking and multimedia art?

Graham Kolbeins: Hi Kyle! Well, movies have excited me ever since I can remember. In high school, I made my friends act out my melodramatic screenplays, and went on to study film and video at CalArts for one year before dropping out. I couldn’t really afford art school and felt more interested in jumping into the experience of working on sets in whatever way that I could. So I did that for a few years, paying rent as a production assistant and a background actor on a variety of projects, and getting some firsthand experience with how movies are made.

In my early 20s, I started making short documentaries and worked on a variety of other creative projects outside of film: writing for magazines and blogs, curating at a not-for-profit art gallery, and starting the fashion/publishing brand Massive Goods with my good friend Anne Ishii (co-producer of Queer Japan). Massive Goods grew our of our work together editing English-language collections of Japanese gay manga, including an omnibus of work by Queer Japan cast member and manga legend Gengoroh Tagame.

KJ: It’s very clear that Japanese art and queer culture had a great impact on you and influenced you to make this film. How long have you been into Japanese art, and do you have other works that are influenced by the culture?

GK: Oh gosh, Japanese anime and manga were everywhere in North American pop culture during my childhood. I fell in love with Sailor Moon (one of my earliest TV obsessions), the films of Hayao Miyazaki, and existential sci-fi epics like Akira, Evangelion, and Ghost in the Shell.

In terms of queer culture from Japan, my introduction was in my teens, when I was having a hard time finding a reflection of my experience as a queer person on TV or at the movies. Was I a “Will” or a “Jack”? There seemed little room for anything else.

So it felt like a revelation when, scrolling through LiveJournal, I stumbled across the artwork of Gengoroh Tagame, Jiraiya, and the other great gay manga artists of G-men magazine. Seeing these gachimuchi (muscle-chubby), burly bears portrayed so lovingly on the illustrated covers of G-men opened up a world of possibilities for me.

About a decade later, I was perplexed that no North American comics publishers had released English translations of these artists’ work. My initial plan was simply to do interviews with a handful of gay manga artists and pitch them to magazines or blogs in an attempt to raise awareness about their work. I reached out to Anne Ishii for help as a translator, but Anne came back to me a much bigger and better idea: a book proposal that would become the two collections The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame and Massive: Gay Erotic Manga and the Men Who Make it.

We traveled to Tokyo together in 2012 to meet and interview the nine artists in Massive, and it was on that trip that I started to gain a deeper understanding of the realities of LGBT+ life in Japan. We were frequently told how stifling the workplace can be for queer people in Japan, due in large part to a lack of non-discrimination protections.

At the same time, I was dazzled to see the scope and breadth of LGBT+ culture in places like Shinjuku Ni-chome, an area in Tokyo with more than 300 bars catering to the queer community. I tried to capture the nuance, diversity, and resilience of that world in Queer Japan.

KJ: That sounds like an amazing experience, for sure. I love that you used the word “queer” as opposed to any other variation. What does “queer” mean to you?

GK: It’s a polarizing word, but I’ve come to love and cherish “queer,” both on a personal level, as an empowering label I use to self-identity, and as a versatile umbrella term for innumerable expressions of non-heteronormative sexualities.

I didn’t always love the word “queer”! Coming of age in the 2000s, there was a long, arduous fight happening for same-sex marriage rights unfolding in the United States. Despite the virulent homophobia of the Bush era, it felt like a time when LGBT+ people were moving toward mainstream acceptance and “normalcy” in society.

I didn’t like being feared and hated so, at first, the idea of assimilating into the dominant culture felt alluring to me. Of course, the window of assimilation only opens so wide, and there’s only so much acceptance on offer. The political movement and LGBT culture at that time were driven largely by respectability politics and tended to erase BIPOC, disabled people, fat people, sex workers, immigrants, trans and gender non-conforming people.

Reading queer and feminist theory helped me undersand the intersectionality of all these stuggles, and the strength that can derived from embracing one’s difference. The more I met queer people who were unapologetic about their queerness rather than trying to conform to the strict standards of heteropatriarchy– the more I found recognition and strength in the term “queer.”

KJ: Why did you think it was important to make “Queer Japan, and what do you hope audiences all over the world can take from “Queer Japan”?

GK: I wanted to throw a spotlight on the amazing artists and activists in this film– just a few of the luminaries who make queer culture in Japan so vibrant and exciting– and share their voices with audiences around the world. I hope viewers of Queer Japan will find a chance to reflect on nuances and variations of gender and sexuality that exist in the world and in their own lives.

Queer Japan is now available in virtual cinemas. Visit queerjapanmovie.com for more info.

Watch the trailer for Queer Japan below!