Bear Tracks: The cultural Influence of BEAR Magazine

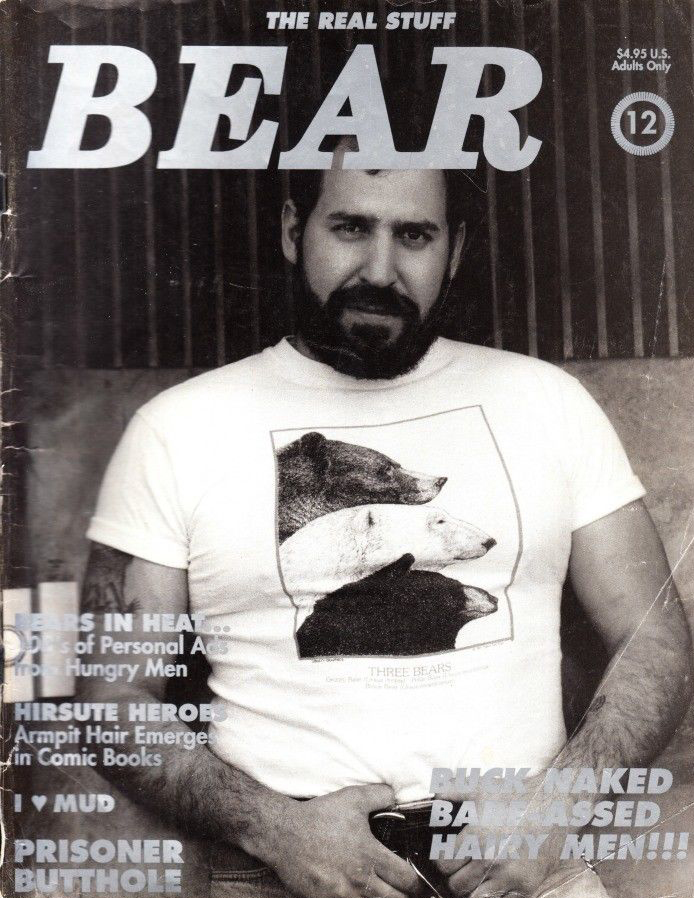

In 1987 I came across a photocopied ‘zine in a gay bookstore in San Francisco. Popular in the 1980s, zines were magazines

produced by an individual or small group of people and photocopied in small quantities. They are of historical significance because they are traces of marginalized communities, of isolated individuals or groups seeking to express and pursue common ideas and values. They were rarely produced with an eye on making a profit. The Internet replaced print publications with websites providing virtually cost-free public circulation, which are easily tracked down with google searches.

Among the rows of zines in a magazine rack at A Different Light bookstore on Castro Street I came across BEAR magazine number 1. Only 45 copies were printed. At that time I often spent afternoons sitting in the front window of Without Reservation, a gay restaurant on Castro Street. It was a great way to hang out right on the main foot traffic thoroughfare that was Castro Street. For the price of a bottomless cup of coffee I could people watch, which included following gay men “walk the loop,” circling around the block cruising for sex. I held court from this perch, greeting and chatting with many gay men I knew from the neighborhood, from gay AA, and other from other gay social circles. I showed my copy of this zine to John Musselman, the friendly, bearish-looking waiter at Without Reservation who served the tables in front of the bar. He told me there were private sex parties where I could meet these guys and others who were calling themselves bears. (I later became fuck buddies with John and his lover. Years later, when they moved to Los Angeles, John sublet his Noe Valley apartment to me and became my landlord.)

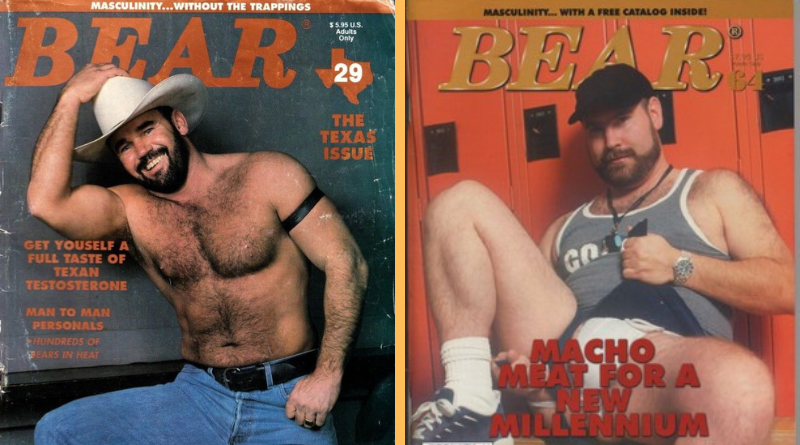

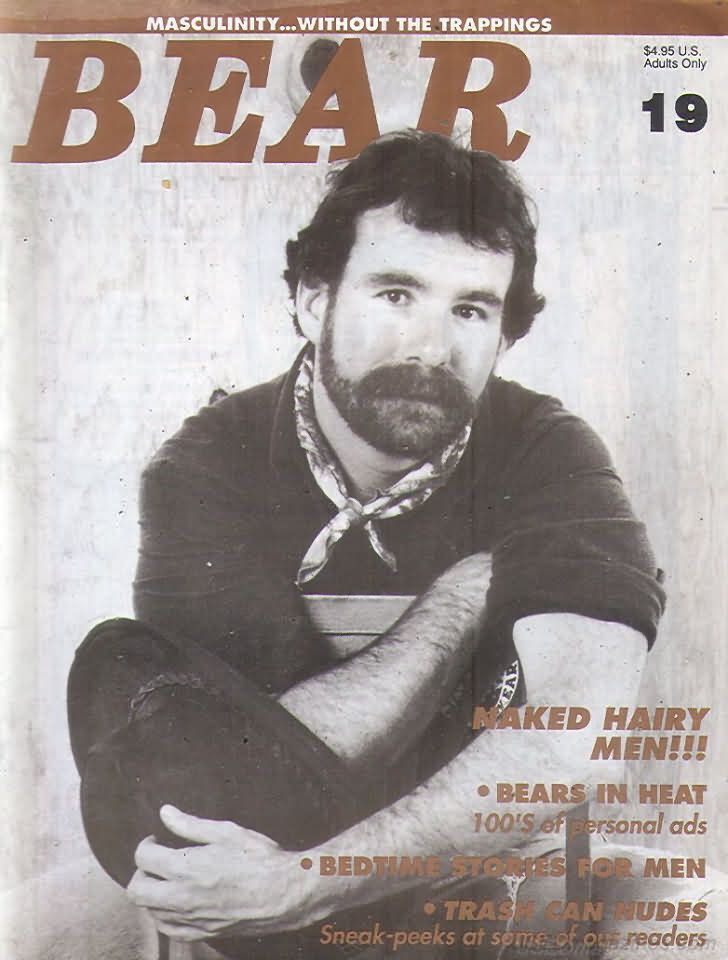

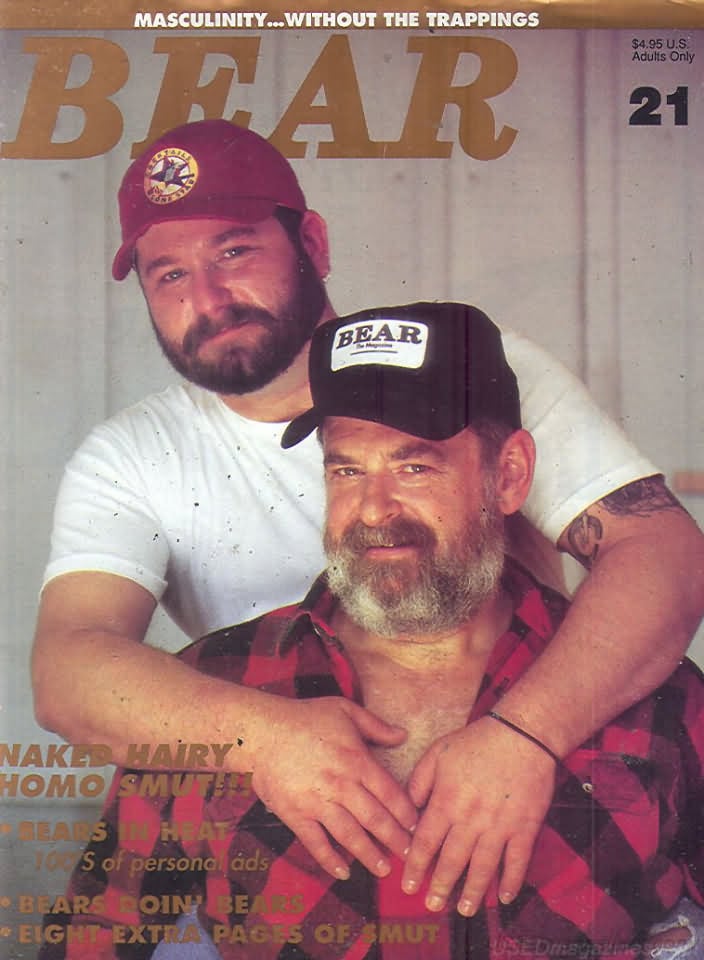

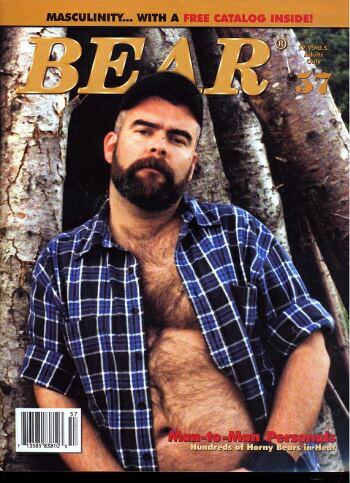

BEAR was printed on 8½ x 11 inch photocopy paper, folded in half and stapled in the middle. It contained mostly nude photographs of ruggedly handsome men (some more attractive than others), some hairy, some tattooed, some burly, some not. These were men you actually saw in the world but never in glossy gay magazines. A guy named Richard Bulger, who was running a talent/model agency looking for men for videos and magazines–and his lover Chris Nelson, a budding photographer–were drawn to the “disenfranchised gay men of San Francisco” (as Luke Mauerman, former columnist for BEAR, wrote). Richard recruited his models off the street and invited them to the editorial office to drop their jeans. He often explained that the idea for his magazine came from a conversation he had had with David Grant for a publication Grant wanted to call “Daddy Bear.” The conversation allegedly took place shortly before Grant’s death from AIDS. In his essay in The Bear Book Luke Mauerman repeated this story. After the publication of The Bear Book, he admitted the story was pure myth.

Over time the BEAR office became a kind of Andy Warholish Factory, Warhol’s legendary studio in New York City, where plenty more went on than just work. The first time I went to the office to ask Richard if I could write a column for BEAR, he took me into his private office, showed me equipment which allowed him to capture images from videos, and explained his vision of BEAR. He told me he wanted to model it after Playboy magazine, intending it to embody a philosophy expressed through photos and serious essays. He had me drop my jeans and offered me the chance to write a column in the spirit of his Playboy philosophy. My first, and only, column, was a film review. After that it was dropped, as Richard explained, because it was taking up advertising space.

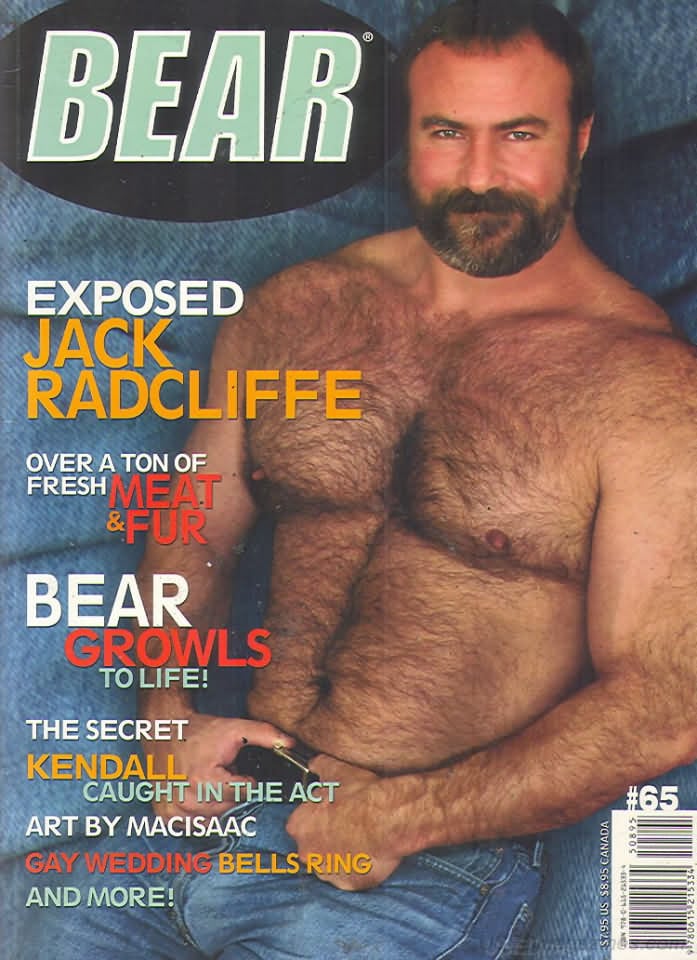

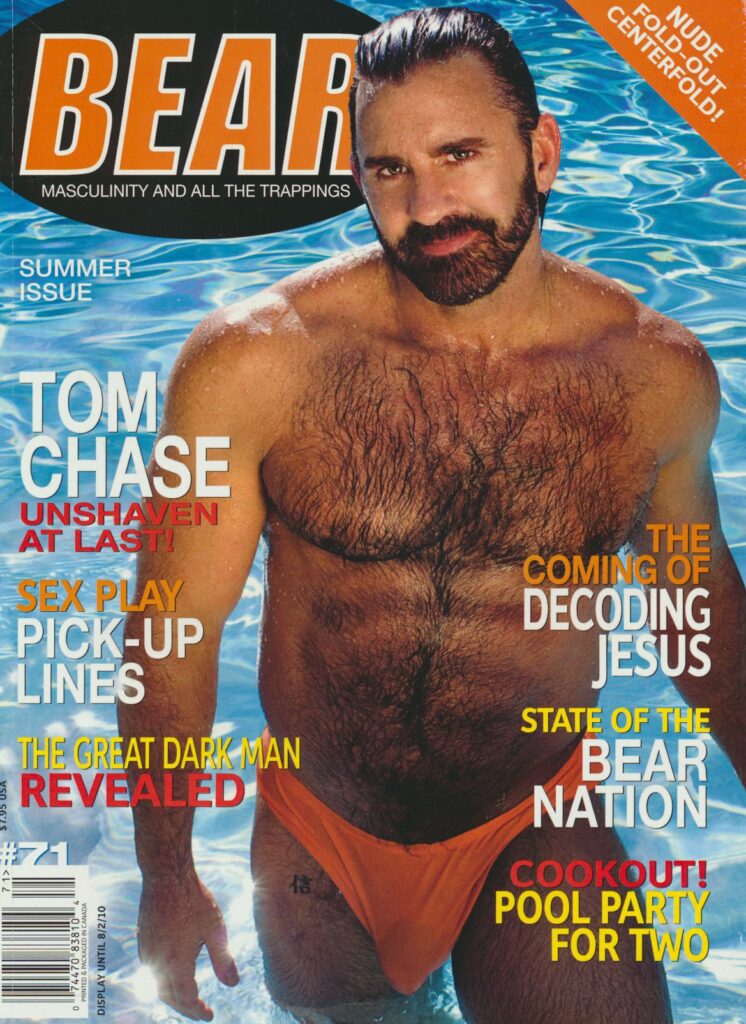

BEAR magazine’s circulation grew rapidly. The format was changed to a standard magazine-sized format, at first with a glossy black-and-white cover, and then a color cover. The shift from “gritty” men to solidly “bear” type men—and the shift to masculine, classically handsome bearish men—was completed when Jack Radcliffe (Frank Martini) graced the cover of issue 9 (1989). He had been the discovery of Chris Nelson and was featured in Nelson’s coffee-table-sized The Bear Cult photo book. This collaboration between Chris, Richard, and Jack established the now iconic imagery of gay bear culture. Quickly pronounced the iconic muscle bear, both Erick Alvarez and I, independent of each other, heralded Jack as the Marilyn Monroe of bear culture. I only ever met Jack once, when he was working as a bartender at the Lone Star Saloon. A highly intelligent man, Jack was academically trained in mathematics and physics. He worked for a software company before becoming a real estate agent, first in San Francisco and currently in Palm Springs.

Bulger inadvertently instigated the “bear wars.” This term has been applied to two separate issues. The first was Bulger’s attempt to copyright the word “bear,” in an attempt to make more money by charging all the bear clubs that were springing up for using the word “bear.” The courts rejected his case, stating that “bear” was a generic, and therefore uncopyrightable, word. The second bear war arose after the appearance of coverbear Jack Radcliffe. The early understanding of a bear had been rather ambiguously broad. The appearance of the muscle bear led to a challenge to redefine bears as muscled and more traditionally handsome. For a while, these camps bifurcated, with muscle bears ascending in the public eye.

At this point I backed away from my bear work. Many first-generation bears also left the bear community. Mind you, I love me my muscle bears, but not at the expense of remarginalizing “average” bears. At one point I attended a Provincetown Bear Week where I saw a sea of Jack Radcliffe look-alikes and was dismayed at what appeared to be the victory of the A-list bears. In fact, part of bear wars included arguments over who counted as a “real bear,” and who exactly the self-appointed arbiters of deciding such things were. At a later Ptown Bear Week I learned that what I had witnessed was due to the fact that a muscle bear event in California had been cancelled and all those guys had decided to go to Ptown instead. I am happy to report that both sorts of bears, as well as numerous more stripes of bears, more or less harmoniously with each other.

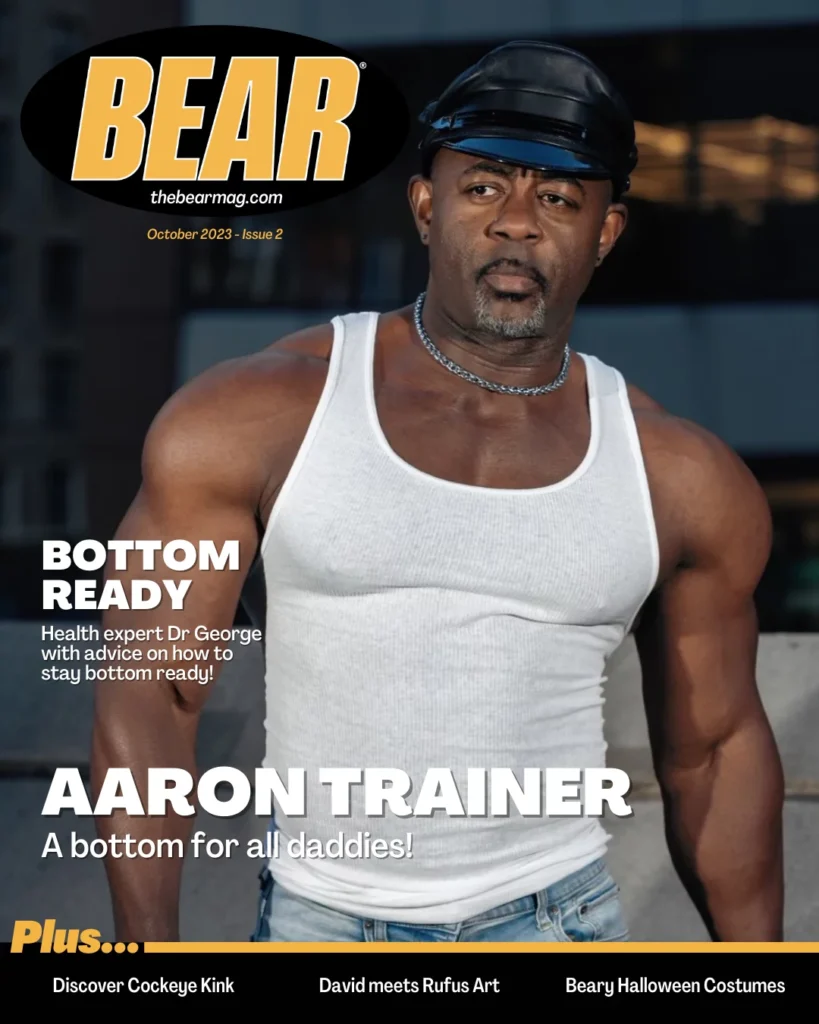

BEAR was published as part of Brush Creek Media, which also produced numerous bear porn flix. In 1994 Beardog Hoffman purchased Brush Creek Media and expanded its scope to include several special interest gay magazines and videos. In 2002 the IRS seized BCM’s inventory, forcing the magazine to shut down. The owners of Butch Media Ltd., a creditor of Brush Creek Media, obtained all copyrights and in 2010 Las Vegas-based Steven Wolfe and Teddy Marke changed the focus of the magazine to cover broader aspects of gay masculinity. (My original offer to write an essay about “the bear as gay icon” for this new publication was accepted. In a follow-up email six months later, they informed me that my writing was not suitable to their needs.) My recent online searches to locate this Las Vegas incarnation of BEAR all directed me to Bear World Magazine, which covers bear culture in its full international scope. Latest word is that BEAR has recently been relaunched under new ownership and can be found at thebearmag.com.

Before moving on from Brush Creek Media, I would like to let readers know that a large collection of Brush Creek Media/Le Salon Media Archive of Gay Film Productions 1970s—1990s is currently for sale from Kayo Books (https://www.abebooks.com/Brush-Creek-Salon-Media-Archive-Gay/31517416120/bd) for $9,900. If there is a sugar daddy bear interested in obtaining this for the Bear History Project International Archives, we would be very glad to hear from you.

Help Les K Wright in his quest to document bear history by joining the Bear History Project International where you and a group of like-minded individuals can exchange ideas and help to preserve bear history and culture.