Bear Tracks: Cybearspace, Personal Ads and the Bear Code

Once upon a time, for a long time before the advent of the Digital Age, gay men placed personal ads in magazines and newspapers to find a romantic or sexual partner. For those who did not live in larger cities this was often the only way to find a partner. It has been estimated that the earliest personal ads were published in the 1690s in England. For a long time this approach was disreputable among respectable people. A woman named Helen Morrison posted an ad in 1727, which came to the attention of the mayor of Manchester, England. He had her committed to an asylum for a month.

The early years of The Advocate, when it was printed in tabloid newspaper format and functioned as a gay movement voice, covered events important to the gay community, along with arts and culture. It was published in two sections. The second section, which could be discreetly removed, contained sexually explicit ads and personal ads. The reader would write a letter (and usually include a photograph) to the newspaper and write l the corresponding code number of the advertiser on the outside of the envelope. And then hope for a reply. This method is still used by the New York Review of Books, which has long published personal ads including from queer people.

Things speeded up when gay newspapers, such as The Bay Times in San Francisco introduced a phone calling system which allowed the anonymous advertiser to retrieve voice messages. For those with deeper pockets video ads became popular in the 1980s.

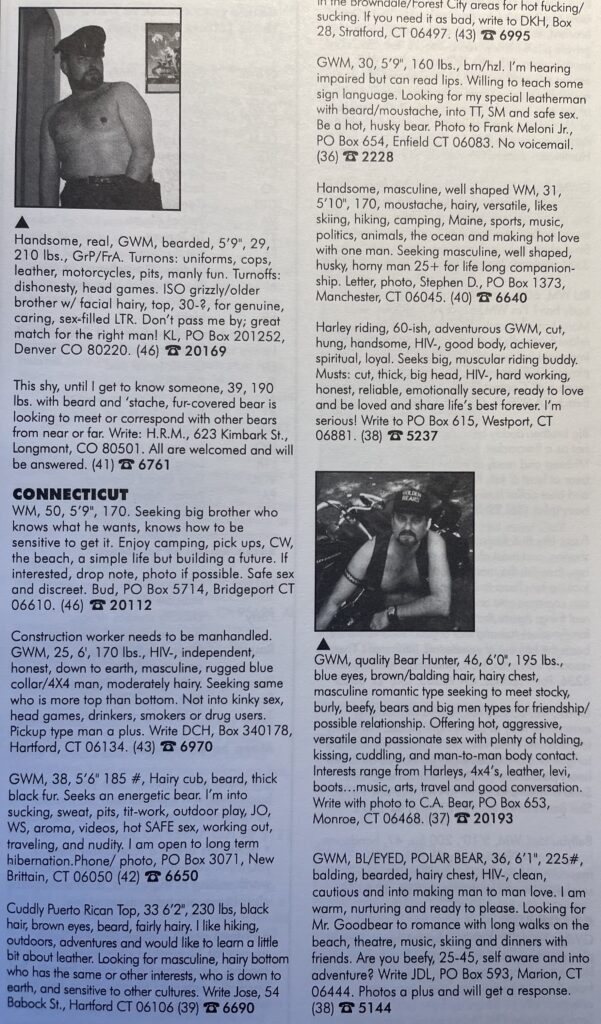

The history of personal ads among bears began with BEAR magazine in the 1980s. It was originally a photocopied ‘zine, featuring nude photographs of scruffy and other “naturally masculine” gay men, offering an alternative to the buff, slender, smooth-skinned models that graced the pages of other gay publications. It also featured free personal ads, which required replying to a coded advertiser. The first issues of BEAR were sold locally in San Francisco. The models were local. And it was an easy way for local bears to meet each other. (I met my third long-term here. Although he eventually married another man, we are still friends.)

Richard Bulger invited men he saw on the street to come in and pose. As BEAR readership expanded, gay men came to San Francisco and went to the magazine’s office in the Mission District (bordering on the Castro District) to be photographed and to network. Jim Maguire, one of my roommates at the time appeared in the magazine. Richard pursued my boyfriend Mike Keating, a San Francisco firefighter, unsuccessfully for his pages. Again the genius of place that was gay San Francisco made all of this feel like a village where everyone seemingly knew everyone else.

In 1988 Cambridge (MA)–based Steve Dyer created the Bears Mailing List. An early online discussion group called soc.motss was a place where gay men communicated. This predates “live chat” online and was accessible only via email. When Steve Dyer and fellow soc.motss member Brian Gollum met at San Francisco Gay Pride Day in 1988 they came up with the idea of creating a BBS (bulletin board system) for guys who were starting to identify themselves as bears to connect.

When Brian mentioned the BML in Drummer magazine in 1990 word was out. The BML became a forum for bears and bear enthusiasts from around the world, as far away as Japan, to connect. In these heady early days, before the rise of bad-faith scammers, the BML was a very friendly and safe social crossroads. Friendships were made. Bears traveling to other places networked with locals who often opened their homes to the visitors, and more friendships arose.

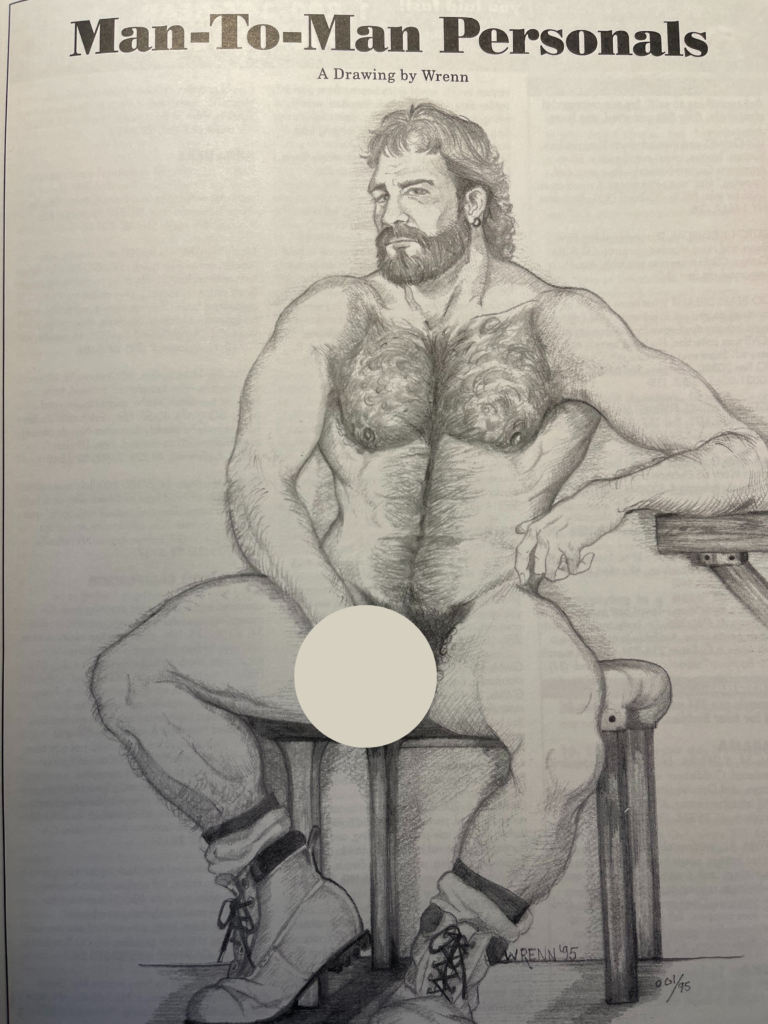

In the 1980s there was no way yet for anyone to send photographs of themselves through email. In 1989, while having a Thanksgiving lunch at a Wendy’s in Boulder, CO astronomy enthusiasts Bob Donahue and Jeff Stoner struck upon the idea of creating a classification system for bears based on the star and galaxy classification system. They were well aware that self-identifying bears came in all shapes and sizes, and created a system broad enough to include nearly everyone. Using letters and plus and minus symbols, this code allowed bears to describe the presence and length of facial hair, body hair, height, weight, cub/daddy dynamics, their “grope factor,” kink interest, muscles, endowment, relationship status (from monogamy to open relationship or polyamory), whether they were eccentric, and “the Q factor”—whether they were, ahem, screaming queens or not. All this easily telegraphed an approximate idea of who they were in the bear world. There was also a “behr” factor category for bears to indicate if they were smooth-skinned. It even became common practice for bears to include their bear code in the signature file of their email.

(I am currently single and still hoping to find my one true husbear. My bear code is B5 f t w+ dc g++ k+ s+ m r- p.)

Help Les K Wright in his quest to document bear history by joining the Bear History Project International where you and a group of like-minded individuals can exchange ideas and help to preserve bear history and culture.