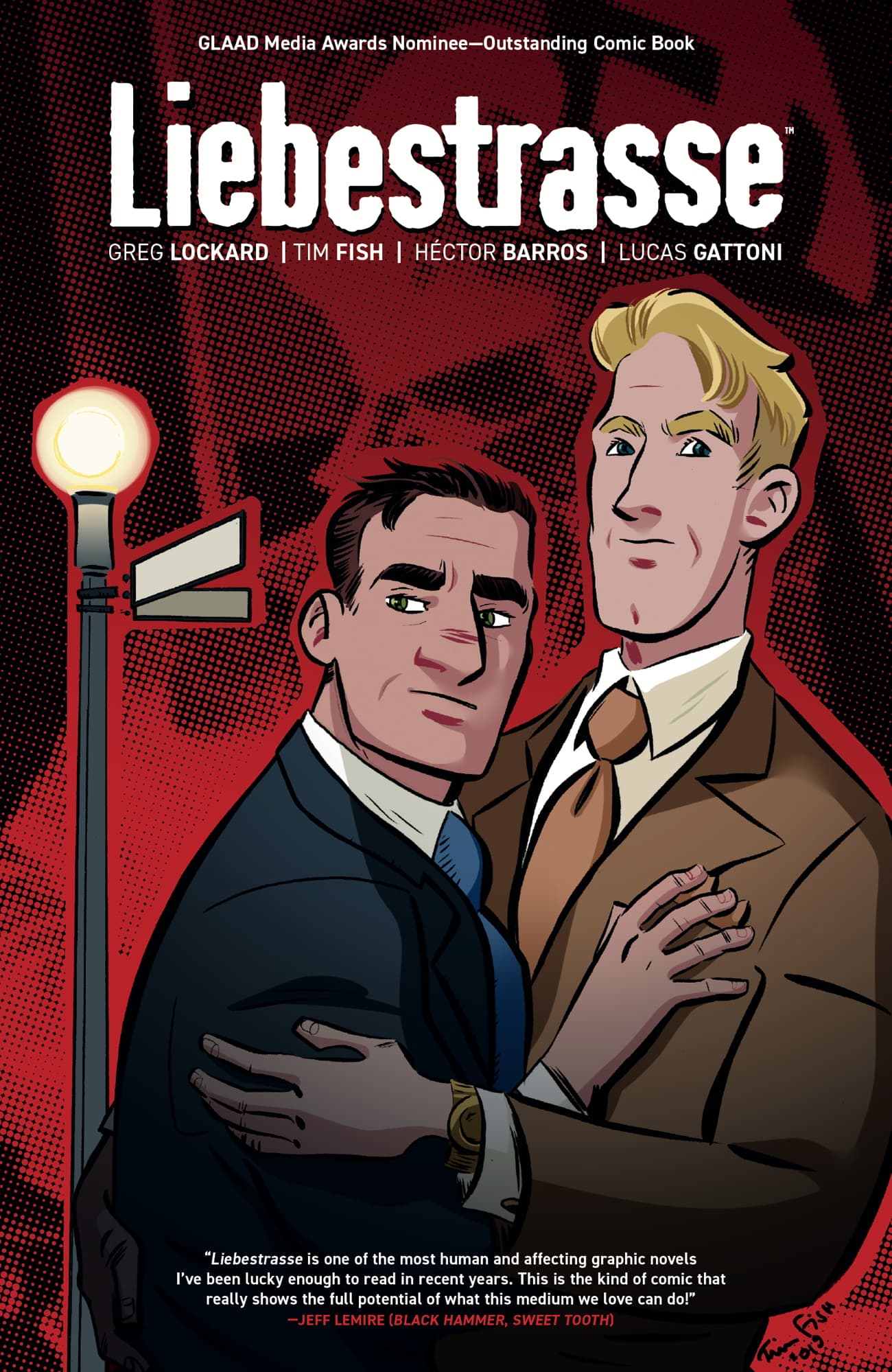

Comics Corner – ‘Liebestrasse’ is a World War II gay romance with a warning from history

Media focused on World War II often focuses on the actual war years of 1939-1945, exploring in broad strokes the horrors of Nazi Germany at the zenith of its murderous regime. Less common are the interwar years, with the slow burn, creeping terror of rising fascism, the people victimised in its wake, and the complicity of the populace along the way. Liebestrasse – literally “Love Street” – is one of those rarer tales.

Focusing on the romance between American Samuel and German Philip in the last days of the Weimar Republic, the graphic novel explores how the two men fall in love, navigating both their cultural differences and the Bohemian underworld of Berlin’s 1930s art scene, and how the rise of the Nazis puts them and everyone they care about in danger.

It will not surprise anyone with a modicum of historical knowledge that Liebestrasse does not have a happy ending.

Published digitally in 2019, and now collected in print by Dark Horse, Liebestrasse – written by Greg Lockard, with art by Tim Fish, colours by Hector Barros, and lettering by Lucas Gattoni – reads with the authenticity of memoir. Bookended by scenes in 1952, where Sam is an art dealer putting together an exhibition of German works from the interwar period, readers are transported back two decades to 1932, to when he first arrived in Berlin.

Then a banker setting up an office to invest in the rebuilding of Germany in the wake of World War I, the early chapters have an almost hopeful whimsy to them, as Sam is swept up in the energy and excitement of Europe, its history and culture. A quiet – what we’d probably now call closeted – gay man, Sam “socialises” with the locals, but when he crosses paths with Philip in an art museum, a deeper connection is forged.

Soon, the pair are inseparable, with Philip introducing Sam – his “cowboy” – to his world of conversational salons, dazzling soirees, speakeasy bars, and his artist sister Hilde. What may be surprising to modern readers is how open the Berlin of the 1930s appeared to be to the idea of two men in love, at least in the circles Philip travels in. While Hilde remarks that Sam brings out “irrational feelings from my brother”, the impression is more that any emotional display is what’s irrational, rather than the couple’s homosexuality.

However, Liebestrasse also explores how gay men had to navigate the firmly heterosexual world of high society. In more public settings, the classically handsome Philip enters parties with beautiful women draped on his arms, while Samuel is keen to avoid any word of his “close friendship” with Philip reaching his American boss.

From the moment they meet, Philip is shown to be more of a firebrand than Samuel though. While Sam is willing to live in the shadows and play things safe, not making any waves, Philip holds court amongst friends while speaking out on the political manoeuvres of the nascent Nazis, who sought to blame minority groups for the country’s state following the Treaty of Versailles that marked the end of the First World War. He openly decries the “arrogant stupidity that surrounds us” despite Nazi supporters being in earshot, and willingly upsets a dinner party with abrasive conversation on how “any neutrality will kill us all”, when it comes to rich financiers refusing to take a stance on the creep of fascism.

Perhaps most powerfully, he chases off a group of Hitler Youth as they attack an older Jewish man, a moment that marks the tipping point of the regime’s rise to power and the emboldened violence of its followers. Even then, Philip refuses to hide away, continuing to frequent underground queer bars and live an authentic life, even after a raid on a jazz club by the SS that puts him and Samuel on the Nazis’ radar as “degenerates”.

It’s a choice that results in him being dragged away by Nazi officers, while Sam is arrested and left to fret over Philip’s fate, before ultimately being deported back to America. It’s one of the most chilling scenes of Liebestrasse – Philip is thoroughly disappeared, never seen again after the arrest. It’s a moment torn from the history books, where anyone who was deemed critical of the Nazis was ripped from their lives. While Philip’s fate is unrevealed, those who read the last Comics Corner on Sins of the Black Flamingo will have a dark understanding of what likely happened to him – and it hits like a punch to the gut.

It’s easy to understand why stories like Liebestrasse are so rarely told, compared to the more common blockbuster epics about storming Normandy or attacks on Pearl Harbor. Unlike those narratives of bombastic heroism, all peppered with explosions and gunplay, stories like this make for uncomfortable reading. Being confronted by a mostly docile public’s ignoring of (or worse, agreement with) rising fascism challenges the audience’s own sense of self, asking them to consider how they might act if placed in similar situations, and many might not like the answer – especially when we’re seeing distressingly similar situations repeat in the present day.

Lockard’s script is peppered with Philip and Hilde’s critiques of how “fellow Germans just fall in line” with the mounting atrocities they’re told to accept, a dark mirror to people’s acceptance of the creeping rightward trend in the here and now. In many ways, Hilde is even more of a canary in the coalmine for the terrors that were coming – as Philip suggests that “the people are organising” in opposition to the Nazis, Hilde laments “not fast enough”. There’s also a palpable sense of fear borne from people being turned against each other – when Samuel is arrested, Hilde is compelled to ask if he gave up any of their friends’ names – and of frustration at the inaction of authorities, with the American Embassy refusing to do anything to protect Samuel or to help Philip, for fear of creating an incident during “a very sensitive diplomatic period”.

Elsewhere, characters’ discussions of book burnings, bans on art considered to be seditious, raids on minority spaces, and people being stripped of citizenship could all be copy-pasted into a modern day story with alarming accuracy. Along with Fish’s artwork, channelling Darwyn Cooke’s elegant, classic style to present the best and worst of the period, makes Liebestrasse an incredibly powerful and timeless work.

Liebestrasse is many things. A beautiful, authentic gay romance. A tale of aching, profound loss and regret. A glimpse of hope from the interwar years, snatched away by hate. But most importantly, it’s a warning – powerfully relevant and incredibly profound, and one of the most important graphic novels you’re likely to read.

This article was originally published on our sister site, Gayming Magazine.