Comics Corner – Be gay, do crimes, with ‘Sins of the Black Flamingo’

The “gentleman thief” is a classic archetype in literature – highly skilled, charming, and usually driven by a personal code of ethics rather than anything so vulgar as greed, they’re often the ultimate villains you love to hate, enacting elaborate heists before making a daring getaway. From the original Arsène Lupin through to the likes of The Saint, Danny Ocean, or even the X-Men’s Gambit, they’re also often portrayed as ladies’ men, leaving a string of besotted lovers in their wake.

However, the gentleman thief has also long been queer coded, typically presented as foppish effetes or bored intellectuals from the bourgeoisie or aristocracy in their civilian lives, and regularly ever-so-slightly (at least) flamboyant in their behaviour. It’s even optional whether they have to be “gentlemen” thieves – vampy female characters such as DC’s Catwoman and Marvel’s Black Cat also fit the mold (and unsurprisingly have strong LGBTQ+ fan followings), while one of the earliest examples of the form is 1915’s silent Italian film Filibus, which followed a female sky pirate who pursues a lesbian love interest and uses a variety of male and female identities to commit her crimes.

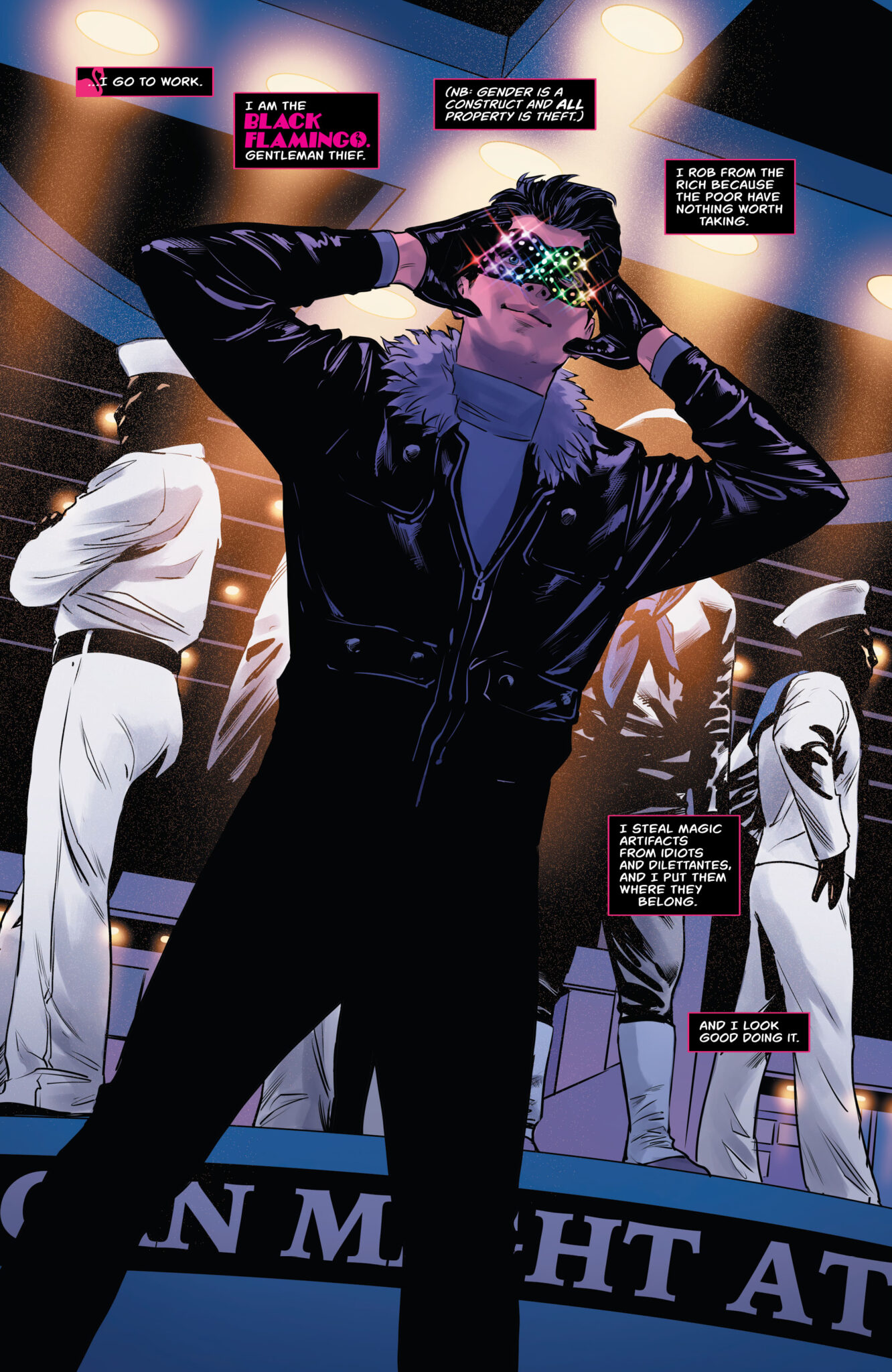

Fast forward to 2022 and Sins of the Black Flamingo is ignoing the genre’s subtext and practically screaming “gentleman thieves are gay, get over it.” Created by writer Andrew Wheeler, artist Travis Moore, colourist Tamra Bonvillain, and letterer Aditya Bidikar, the new Image Comics miniseries follows the overtly, openly, proudly gay Sebastian Harlow, who ‘acquires’ rare objects under the titular nom de voleur.

He does it all in absolute style too, committing his daring robberies in a chic black outfit with a fur ruff, and a fabulous domino mask kitted out with rainbow reflectors. It’s not just a lewk though – the hi-tech facewear also scrambles facial recognition, preventing Harlow being caught on camera as anything more than a sparkle-topped shadow.

However, Harlow isn’t quite a Robin Hood type – he “robs from the rich because the poor have nothing worth taking”, and the objects at the heart of his heists are usually of a more supernatural persuasion. He’s not above taking on the odd commission though, and the first issue opens with him accepting a request from a Rabbi’s grandson to steal back the animating soul tablet for a World War II era golem, held in an underground Nazi memorabila collection.

Wheeler uses the scene to introduce the Black Flamingo’s more nihilistic personality traits – a reflection that the Nazis were “the surest sign that humanity was a mistake” is the first of several instances of Harlow’s seeming disdain for people in general. It also serves up a lesson in real world queer history, reminding readers how, when the Allied Forces ‘liberated’ the concentration camps at the end of the war, the gay men there – identifiable by the pink triangles they were forced to wear – were sent back to prison for the ‘crime’ of simply being gay. “That should give you a good sense that people, as a rule, are worthless”, Harlow reflects – and it’s hard to know that historical fact and disagree.

Indeed, there’s a cynical strain of social commentary laced through the book, with the Florida setting offering the perfect framing for observations on contemporary societal decline, contrasting the sheer weirdness of the Sunshine State – insert Florida Man meme here – with the almost fetishised level of faux-patriotism infecting corners of modern America, and atop it al, as Harlow puts it, a “heterosexual elite that model[s] their luxury on despots and popes”. There’s also a frustration that bleeds through, with Harlow – seemingly a man of some means, befitting the gentleman thief model – detesting the same people he seems to spend the most time with through his day job as a specialised antiques dealer, travelling in the circles of Florida’s gauche ultra-wealthy.

The one person Harlow seems to enjoy the company of is Ofelia, equal parts aide-de-camp and advisor to his activities as the Black Flamingo. She’s a confidante, knowing of the mystical nature of Harlow’s targets, and his own strange visions that – at least so far as readers can figure from this first issue – show him the truth behind people’s public appearances, perhaps even the nature of their souls. Ofelia has abilities of her own though, not least some degree of spell-casting, and a mysterious creed dictating how she should use them.

Ofelia also serves as something of a moral advisor to the Black Flamingo, displaying a bit more optimism and faith in humanity’s potential. She actively pushes Harlow to “do more good works”, and reins in his more abrasive interpersonal traits around others. We don’t spend a great deal of time with Ofelia in this first issue, but she makes a striking impression, and getting more insight into her both individually and how she came to know and work with Harlow should be a fascinating part of the series going forwards.

Aside from the main narrative, it’s delightful how unabashedly gay the comic is, in both dialogue and visuals. Although Harlow doesn’t have so much as a peck of a kiss with a man here, he leaves no ambiguity he’s gay, with references to spending time in darkrooms, watching Netflix dramas about “beautiful horny Spaniards committing crimes”, and fantasising about flirtatious cat and mouse games with a handsome detective nemesis (that he’s yet to encounter, alas). Along with his disinterest in people en masse, he seems thoroughly dismissive of heteronormativity as a concept.

Throughout, Moore’s art, abetted by Bonvillain’s colours, is an almost criminal thirst trap too. It’s a queer inversion of ‘cheesecake’, or pin-up, style, with plenty of titillating yet tasteful skin on show. Even the cover is undeniably, boldly gay, with the Black Flamingo pairing his signature rainbow mask with an open shirt. It’s still comic art directed at the male gaze, but very specifically the gay male gaze, which is still a rarity. Moore and Bonvillain’s work also shines for the darker, more magical elements of the book, particularly the body-warped horror of Harlow’s visions and a last page twist that readers won’t see coming.

Ultimately though, what makes Sins of the Black Flamingo stand out though is how sadly relatable Sebastian Harlow is as a character. While the wider story is shaping up as a slice of magic realism blended with a powerful dose of queer rage, Harlow’s fatalism is all too easy to connect to. Anyone who reads the news and despairs at the various political and social powers-that-be refusing to act on any number of existential issues, or who is exhausted at having to fight daily battles just to exist, will find common ground in Harlow’s view that “empathy is exhausting, most people don’t deserve it, and everyone is doomed already.” Given Wheeler’s other works – and even Harlow’s actions in this issue despite his words – are more positive though, we look forward to seeing how the light of optimism may creep into the Black Flamingo’s dark world over the course of the series.

As an opening issue, Sins of the Black Flamingo #1 keeps a lot of cards close to its chest. There’s no hint yet of where Sebastian’s abilities come from, what his connection to Ofelia is, or even what those eponymous “sins” are – merely his high level thefts, or something else, something perhaps darker? However, the very fact that we’re left wanting answers to those questions after the debut alone is the sign of a great comic.

Sins of the Black Flamingo is out now, published by Image Comics, and available digitally and in print.