Bear Tracks: The Life and Work of Leathersex Pioneer Jack Fritscher

Jack Fritscher (b. 1939; PhD, 1967) is best known for his pioneering role in the leathersex community. His presence and work on page and screen—in fiction, nonfiction, erotica, photography, and video — has been ubiquitous in American and international gay culture for decades. As an eyewitness, he has experienced and documented American gay history from the rise of the motorcycle-and-leather scene after the Second World War to 2023. His twenty books include six novels with two set inside the epidemics of AIDS and Covid: the sweeping history of his Lammy Finalist, Some Dance to Remember: A Memoir-Novel of San Francisco 1970-1982, and the intimate Castro Street Blues: A Covid Comedy of Gay San Francisco.

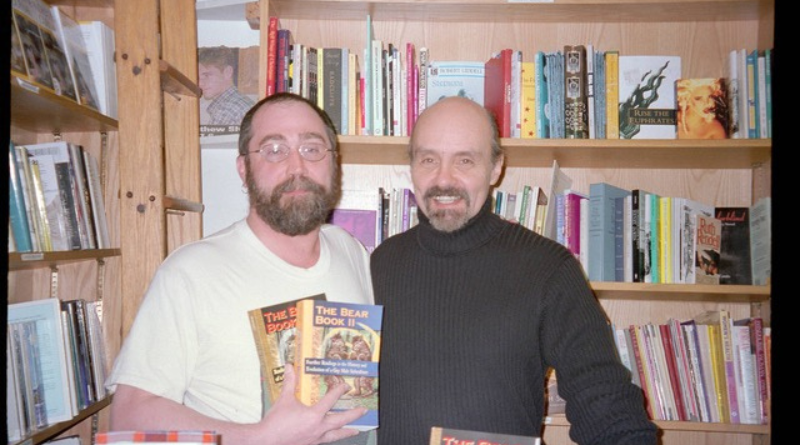

Fritscher, with four nonfiction books of gay history, fleshed out his “Bear Genome Project” in his “Introduction” to my Bear Book II. As Jacques Barzun wrote, “Linking is particularly important in cultural history, because culture is a web of many strands; none is spun by itself, nor is it cut off at a fixed date like wars and regimes.” Fritscher connects many of the evolving dots of the appearance of proto-bears before the emergence of self-identifying bears in the 1980s.

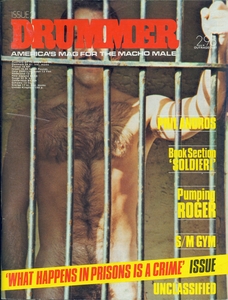

Best known as the founding San Francisco editor-in-chief of the leathersex Drummer magazine, Fritscher, who was first published in 1957, is a pre-Stonewall contemporary of John Rechy, Dorothy Allison, Andrew Holleran, Felice Picano, Edmund White, and other canonical writers who grew up during the Second World War. He was educated in the Irish-Catholic tradition and earned his PhD in literature at Loyola University of Chicago with his gay-inflected dissertation: Love and Death in Tennessee Williams, 1967.

Through the gay physique magazines of the 1950s, like Tomorrow’s Man and Physique Pictorial, featuring masculine, muscular, sometimes bearded and hairy alternatives to the gay stereotype, he broadened his perspective through his embrace of an emerging gay masculinity just on the cusp of the dawning of the age of gay identities in the 1960s. Before Stonewall, as a young university professor in 1968, he was a founding member of the American Popular Culture Association making certain there was a gay plank in the PCA academic platform. He wrote the first gay essays for the Journal of Popular Culture, reviewing Hair in 1968 and The Boys in the Band in 1969.

His writings, personal involvement, and professional efforts are major contributions to documenting the rise of gay popular culture. In 1972, he penned Popular Witchcraft: Straight from the Witch’s Mouth, the first nonfiction gay book to touch on gay wicca, leathersex, and High Priest Anton LaVey. From 1977 to 1980, he was a lover of Robert Mapplethorpe whom he eulogized in his 1994 memoir, Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera. His coverage and involvement in the leathersex community is voluminous and legendary.

Over the years, more than a hundred of his erotic stories have been published in dozens of gay magazines–spreading concepts of leather and bears and homomasculinity to mail-order subscribers stuck in the sticks of America who, dissatisfied because they did not look like the gay models in big-city gay magazines, were in eager search of a gay identity that looked like them.

In 1979, Fritscher coined and published in Drummer the word “homomasculinity” which is a foundational concept of the bear movement. He wrote a new tagline for Drummer, “The American Journal of Gay Popular Culture,” which opened the leatherman magazine up to include other queer identities–thus preparing the way for bears.

In 1980, he founded Man2Man Quarterly (the premiere issue featured a bear on the cover) which San Francisco publisher Richard Bulger (1954-2015) named as a model for his Bear magazine which he founded in 1987. In 1982, just as the 28-year-old trained anthropologist Bulger was settling into San Francisco, Fritscher at 43 published the word “bear”in the “contemporary gay male identity sense” on the cover of California Action Guide magazine which he edited. At the top of the cover, he printed the banner tagline: “Beyond Gay: Homomasculinity for the 80s.”

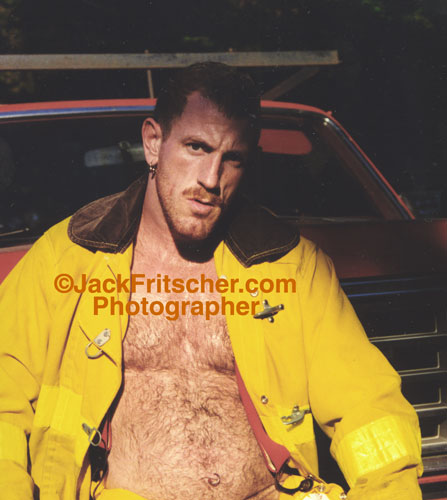

In 1984, with his husband, the bear Mark Hemry, he launched his Palm Drive Video company which produced 150 safe-sex homomasculine feature films just before Richard Bulger, proclaiming bears as “naturally” masculine gay men, began shooting his Brush Creek Media’s bearsex videos to fund the founding and printing of his magazine.

Sorting the roots of bear history from my own experience in my 1995 Frontiers article, I verified Bear magazine as the direct descendent of Fritscher’s Man2Man zine because M2M‘s tagline “What you’re looking for is looking for you” was a beacon of light for me and what I was looking for. Fritscher published my article “Sociology of the Urban Gay Bear,” the first academic article to be published on bears, as the cover article of Drummer, the “Bear Issue” 140, June 1990, for which he shot the cover photo, “Bear Seated in Red Truck.”

Fritscher, who personally videotaped the world’s “first bear contest” at San Francisco’s Pilsner Inn in February 1987, locates proto-bear pop-culture manifestations in San Francisco’s No Name bar and the Ambush bar, in hirsute vintage actors like Clint Walker and Robert Redford, in gay porn star Richard Locke (my Billy brother), and in the hairy blue-collar photos of Old Reliable (David Hurles) among others. Cornell University has acquired Fritscher’s archives.

Up until Drummer closed after 24 years in 1999, Fritscher continued his foregrounding of bearish gay men, incubating bears in word and image, in that iconic magazine where he published Robert Mapplethorpe’s first magazine cover of a bearish cigar-smoking biker on the cover of issue 24 (September 1978). In that issue, he also reviewed the mature hairy actors in the Gage Brothers “Working Man Trilogy” of films, and profiled gay icon Richard Locke as the proto-Daddy making the new late-70s fetish of “Daddies” — which evolved to the fetish of bears — a constant theme in Drummer monthly issues and dozens of special issues titled Daddies.

What is not named cannot be spoken.In 2005, Fritscher presented his paper Homomasculinity: Framing Keywords of Queer Popular Culture at the Queer Keyword Conference, School of English, University of College Dublin, Ireland. In it, he mentioned the word bear more than sixty times.

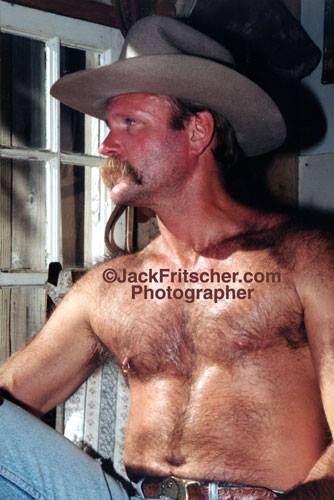

Fritscher reports that “in Drummer 119, 1988, Fritscher produced the thematic issue, “Wild and Wooly Men in the Greats Outdoors,” promoting authentic bear stories and bear videos. He wrote its lead cover article, “Bears and Mountain Men,” based on his twelve summers as a practicing Mountain Man wearing buckskin leathers straight out of J. Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales. He studied and videotaped these contemporary Mountain Men weekends at primitive rendezvous gatherings in the California foothills where he slept in his own teepee and shot black-powder rifles with a posse of straight but friendly blue-collar factory workers and biker bears who, like serious Civil War Reenactors, live the life of Mountain Men on weekends throughout the West.”

In 1995, seven years after this Mountain Man article, his introduction of the word rendezvous into gay fetish vocabulary became part of the title of the famous annual gathering, The International Bear Rendezvous (IBR) sponsored by the Bears of San Francisco. (IBR was the successor to Bear Expo.) The term Mountain Men, preceding bear in the gay lexicon, was first popularized in Richard Amory’s 1966 bestselling novel of gay Mountain Men in love, Song of the Loon, which is another foundational document of bear history.

Mountain Men has an equivalency in the concept of the “lumbersexual.” In The Guide: Gay Bodies and Expressions (2018) Brandon W. Mosley features bear, cub, otter, wolf, leather, and lumbersexual as distinct identities. Interestingly, he states that the lumbersexual is a gay, and not straight, identity. All the lumbersexual men I have seen on the streets of upstate New York cities have clearly been heterosexual (like Fritscher’s straight rendezvous experiences).

Fritscher was a constant supporter of Bulger and his Bear magazine project. With his big Walt Whitman beard, he appeared as the centerfold in Bear 4. He traded models — like “Mike Kloubec” whose legal name was John Muir — with Bulger, hiring several of Bulger’s bears to model for Drummer and for dozens of videos at Palm Drive Video whose tagline was “Masculine Videos for Men Who Like Men Masculine.”

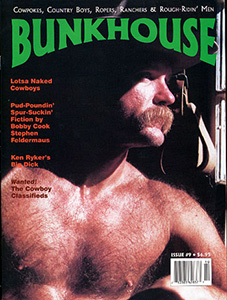

Even after Bulger sold his small business to Brush Creek Media Inc. in 1996, Fritscher remained a frequent contributor to Bear and its brother magazine, Bunkhouse. In 1988, Bulger’s erstwhile partner, photographer Chris Nelson (1960–2006), shot him for the first photo book of bears, The Bear Cult, published in London in 1991. Ten years later, Fritscher curated and produced the first collection of bear fiction, Tales of the Bear Cult: Best Bear Stories from the Best Magazines.

In the literary world beyond the borders of the leather community, Fritscher is best noted for what he describes as his “screenplay novel,” Some Dance to Remember. Hailed by The Advocate as “A gay Gone with the Wind,” this novel, whose antagonist is a hairy blond bodybuilder, is a docu-drama of the San Francisco gay community of the 1970s which legendary writer Sam Steward called “perhaps the great American gay novel.” Boston-based gay culture critic Michael Bronski reviewed as “a novel of ideas.” Some Dance presents an eyewitness account of the Castro in the euphoric and hedonistic heyday of the first decade after Stonewall, and celebrates the “glorious mood swings” of those years bracketed by the June 1969 riot and the AIDS epidemic.

Some Dance to Remember stands in a place of honor in my library, along with John Rechy’s City of Night and Andrew Holleran’s Dancer from the Dance. These three novels are road maps which in brilliant and sometimes brutish detail elevate to the level of myth the three gay worlds that I lived through and was shaped by: pre-Stonewall America, New York City in the 1970s, and San Francisco in the 1970s. Out of this long hibernation, came the bears.

For the sake of full disclosure, Jack has been a personal guide for me through his writings, and a professional guide and unwavering supporter and cheerleader of my work in bear and gay history work. I thank him for clarifying and supplying additional information for this column.

All photos used with permission of Jack Fritscher. Find out more about him and his work at jackfritscher.com.

Help Les K Wright in his quest to document bear history by joining the Bear History Project International where you and a group of like-minded individuals can exchange ideas and help to preserve bear history and culture.