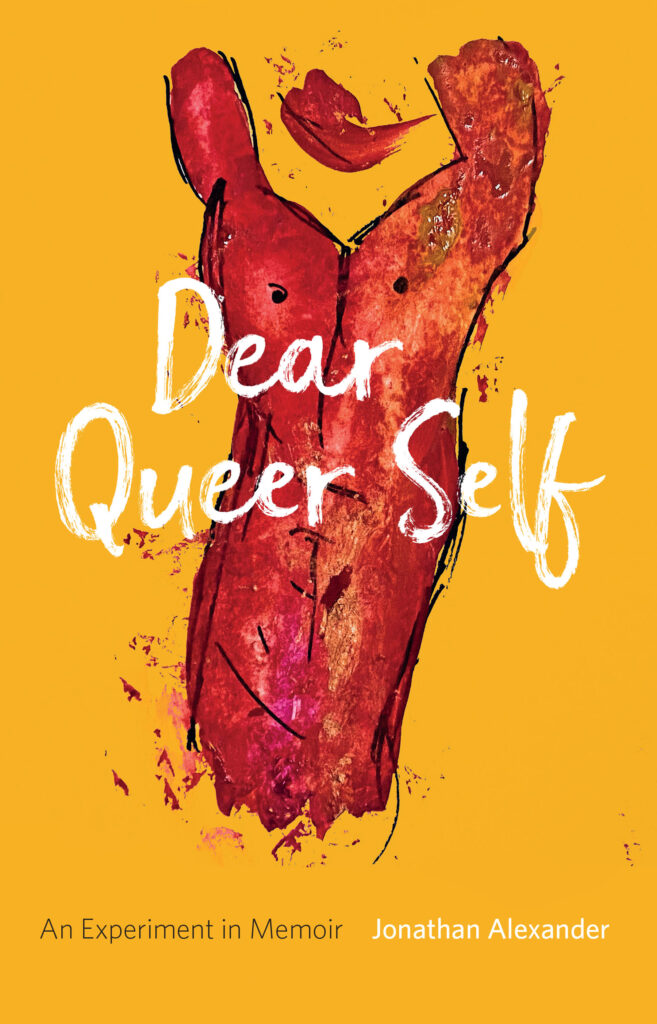

‘Dear Queer Self’: A gay memoir with a difference

Enjoy this excerpt from “Dear Queer Self: An Experiment in Memoir” by Jonathan Alexander, out on March 14 from Acre Books.

“Dear Queer Self” is the third memoir from queer author Jonathan Alexander, and the final book in his Creep Trilogy. The book is written in second person, Jonathan talking to his younger self, and it covers three pivotal years growing up: 1989, 1993, and 1996. The excerpted chapter is “If It Makes You Happy” — Sheryl Crow. Each chapter is named after a pop song of the year being discussed. The book also comes with a a corresponding YouTube Playlist to set the mood corresponding with each of the three years/sections discussed.

Here’s an excerpt from “Dear Queer Self”:

“If It Makes You Happy” — Sheryl Crow

Maybe what you are feeling, for once, is how you are entering history. Of course, you are never not already in it. But when have you had the chance to feel history, and feel yourself, your life, as part of history?

Perhaps you are just getting older. Don’t worry: you are young yet, oh so very young. You have more than enough time to consider the question, which will come to you as surely as your first gray hair: what remains of all that misery, all the history of misery? Your trick, something you’ll accept as a gift, will be to note how misery is never entirely yours alone, to understand that something, perhaps what people call “history,” surrounds you, us, and all of us are swayed by it, that it ripples constantly under and around and through us, moves us gently up and down and from side to side, and then, at times, not so gently, but suddenly, roughly, even catastrophically.

Your catastrophe still awaits you, even though you feel (write it!) like you’re already going through it. But no, not yet.

What you are going through, at this point in the chronology, is the possibility of having a real live gay date. That’s right, and that’s how you’re thinking of it. In your mind, the collegiate, senior-year interlude with Mike doesn’t quite count as your “gay time.” Sure, you were dating a boy, and you were basically “out” to the Film Committee, but so much of that doesn’t come down to you as real. Not really gay. More like playing at being gay. But now, on the other side of your divorce, on the other side of having given heterosexuality a good adult try, on the other side of publicly labelling yourself a “bisexual,” you feel there’s no safety net. Maybe being “out” is a dividing line, after all. (You’ll go back and forth on this for a while.)

As your older self writes this, he is mindful that you have not yet told your parents. Yes, you have told them about the divorce. Mother doesn’t quite say she’s surprised the marriage lasted as long as it did, but there’s relief in her response to the news, as in, Thank god that’s over. She will not ask what’s coming next. Though you don’t think she wants you to be lonely, she seems most comfortable imagining you alone. She just doesn’t like to think of you with a mate. You’re not sure why. But you grasp it’s best to refrain from mentioning that your divorce coincides with your decision to “come out,” to start pursuing a decidedly “gay lifestyle.” She would not approve, even as your father, you instinctively know, would not be especially surprised—and would almost surely not care. But your mother would. In fact, when you’ve been divorced a couple of years and have found the person you’ll likely spend the rest of your days with, you will call her up to talk about him, the man you are dating, and she will interrupt you, pointedly, and say, “I don’t want to hear about the evil in your life.” You won’t be able to respond immediately, and in the silence she will finish her thought with words no child wants to hear, whatever the circumstances, whatever the historical and personal particulars: “We don’t love you for who you are. We love you for the person we know you could be.”

In that moment, you will choose to commit all the more to the life you have chosen—not out of any spite or resentment, but because you will be free, finally and fully free, from any sense that you are beholden to your parents; if they can relinquish the parental prerogative to love unconditionally, then you can relinquish any sense of responsibility to them. This wound—and wound it is, despite the stoicism with which you receive it—will eventually heal. Things will change. Your relationship to both your father and your mother will alter. But that is the subject of a different book. For now, for the you that lies between your just-divorced self and the future self writing these words, there is much yet to experience, much yet to try to understand.

You meet Shawn through Karen. A graduate of the university where you teach, he is her former student, an English major, of all things, and someone still involved in the student lesbian and gay group of which you’re faculty sponsor. He lives in Pueblo and shows up at meetings sometimes, saying hello, offering his thoughts, an older brother’s shoulder. You take note because, well, he’s cute. And not a student. That’s important. You don’t want to be the professor who fucks his students. That’s such a hetero cliché. No need to tempt people to think it’s also a gay cliché.

Ah, the things you need to think about now that you’re queer.

And indeed, you have some gaps in your knowledge base. It’s been a while since you’ve been on a date, since you’ve asked someone out. You don’t know if Shawn’s remotely interested in you. He seems friendly enough, and once you thought you saw him looking at you before quickly turning away. Oh, fuck, you think, so many guessing games. Why can’t we all just wear cards that announce what we’re looking for?

Curiously, you soon realize there is a place where people wear just such identifying cards. It’s called the Internet, and since your divorce, you’ve stuck around the computer lab you teach writing in, waiting until everyone is gone and the room is officially closed so you can, as you say, “catch up on some work,” but really, once the light in the outer hall goes off, you start cruising websites for porn. Gay porn. Raunchy, nasty, cocksucking, assfucking porn. You find a whole ever-expanding world of guys fucking, fisting, tying each other up, and spanking one another. It’s incredible. There’s even a site built around a play prison, with what look like real jail cells, in which men imprison one another, taking turns in bondage gear, teasing and torturing one another, fucking. You’ve hit the jackpot. Even if you don’t know how to do any of this stuff in real life, you can still enjoy it on the screen. You can learn. You see a boy spreadeagled on a bed, facedown, the pixelated image slowly resolving—it is 1996, after all—your right hand clicking on the mouse to download other images in the sequence, such as the bearish top with a paddle poised over the now gagged boy, and with your left hand you reach down to your crotch. . . .

A sudden jangle at the door; a key going in.

Fuck.

You quickly click away from the pages. It’s Heather, the super-smart poet who works primarily as the school’s technology support.

“Hey, didn’t know anyone was in here! Just checking on the server.”

“No problem! Just finishing up some work.”

“Cool, cool.”

She disappears into the backroom to do her thing, and you start to pack your bag. But first you clear the cache. You know enough to do that. And you do it every time—much to Heather’s chagrin, you will discover, because sometimes she goes searching for images she’s seen during her own web surfing . . . But nope. You have learned to cover your tracks. After all, you’ve been doing a version of clearing the cache for years.

Preorder a copy of “Dear Queer Self” by visiting acre-books.com/books/dear-queer-self.

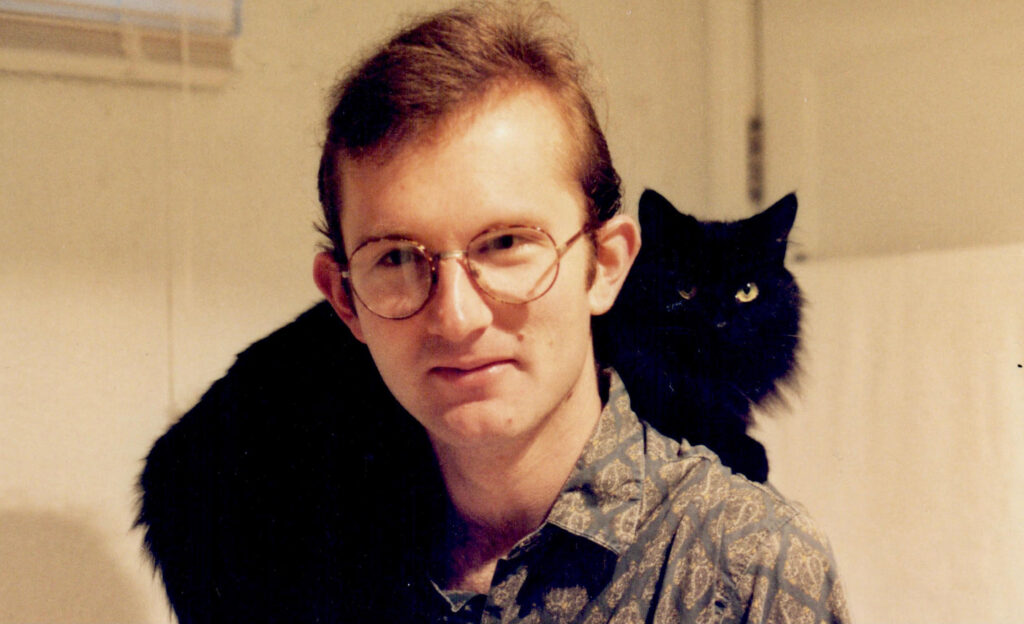

About the Author

Jonathan Alexander is a writer living in Southern California where he is Chancellor’s Professor of English at the University of California, Irvine. He is the author, co-author, or editor of twenty-one books. His cultural journalism has been widely published, especially in the Los Angeles Review of Books for which he is the Young Adult editor, where founding editor Tom Lutz called him one of “our finest essayists.” He lives with his husband and cat, and when not writing, dabbles in watercolors and plays piano in a music ensemble with friends.

More about Jonathan Alexander and his books here.

About Acre Books

Acre Books is the book-publishing offshoot of The Cincinnati Review, a semiannual literary journal based at the University of Cincinnati, founded in 2003.